Jerrems Family Newsletter

Dear Donald,

Jerrems Journal. In other words, we defer on

previously submitted storylines.

We have a pending follow-up story on Alexander

Nicoll from the January issue.

We are

also holding a story line from Leonore Neary

about

Arthur (b1872), “Aunt Mame”, and Aunty Vi (aged

19).

We also have pictures and story line about

William George Jerrems IV submitted by

Sue Jerrems.

And we have a backlogged story with pictures from

Ray Lloyd’s grandmother Elizabeth and her sister

Alice, Daughters of Samuel Jerrams and Sarah

Pritchard.

So, we are a bit in arrears. Keep the pictures and

stories coming; we will get to them. We love the

Remember Us Series.

| Remember Us from the Great War |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian

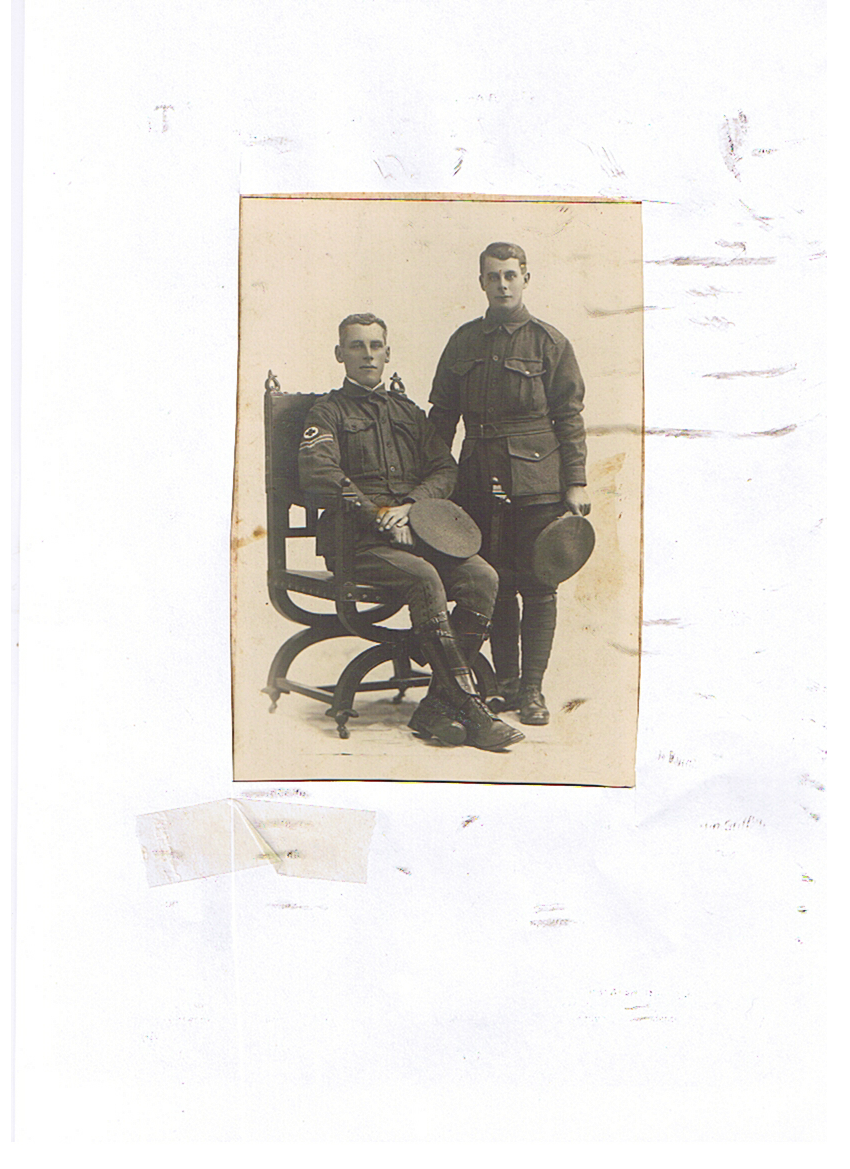

Above is a photo of my grandfather Edward Healy

Smith (sitting) and his brother. My grandfather,

with his trademark lantern jaw, is dressed in the

uniform supplied to him as a member of B Company

in the 13th Field Ambulance Unit. In summary he

served in France in World War l as a stretcher bearer

and was awarded the Military Medal.

But what was the former headmaster of an English Art

School doing in an Australian Army Field Ambulance

unit in the killing fields of France in 1917? Simply, he

had grown up in Templestowe in England in a

strict “Plymouth Brethren” family (the Plymouth

Brethren were what we would now call “conscientious

objectors”). He migrated to Western Australia with his

brother and soon joined up, his concession to his

religious upbringing being that he enlisted in a non-

combative role in the Field Ambulance.

He was probably under no illusion that the job of a

stretcher bearer would be testing, but nothing would

have prepared him for the horror of the war in France. I

cannot say definitely from his war records all the

battles he participated in but I have a note he wrote

when he was resting on the outskirts of Amiens after

the Battle of Villiers Brettoneaux. Later he was

probably also at the Third Battle of Ypres and the Third

Battle of the Somme. The Unit (formed before his

Company joined it) served earlier at Pozieres,

Mouquet Farm, Bullecourt, Messines and

Passchendale.

As an art student he had cycled through these areas

15 years earlier, sketching the cathedrals and other

landmarks. He had won awards for his art. His artistic

temperament was shattered by his wartime

experiences.

One of the only people he ever spoke to about the War

was me, for about half an hour. Here is what he told

me. He said the worst part of his job as a stretcher

bearer was to decide which of the wounded men

could survive their wounds as he threaded his way

between the corpses, the shell holes, the barbed wire

and the wounded. The men who he decided were

beyond help knew that their fate was sealed.

He told me that he had been awarded the Military

Medal (statistically speaking this was awarded to only

approximately one Australian soldier in every 200) for

going out into No Man’s Land under German fire to

rescue wounded Diggers. He went by himself

because nobody else would go. The man with the

lantern jaw (often associated with stubborn people)

had made up his mind, in his words to me he

preferred to go out rather than go insane listening to

the haunting cries of the wounded.

I have not been able to locate the citation for the

Medal, the most obvious way of finding out where he

earned it. However his service record refers to him as

being awarded the MM on 21st April 1918. This

coincides with the first night of the Australians’ attack

at Villiers Brettoneaux, where the Australians incurred

heavy casualties but were spectacularly successful in

achieving their objective of stopping the Germans’ last

major advance. It has been described by some as the

turning point of the War.

The town of Villiers Brettoneux has an almost

legendary status in Australian folk lore. After the War

money donated by school children in Victoria helped

to build the school there. The school was inaugurated

on Anzac Day 1927, and since then every classroom

and the town’s community hall have displayed a sign

that has become legendary in Australia: “N’Oublions

Jamais l’Australie” (Let Us Never Forget Australia).

Australian visitors are warmly welcomed there and the

schoolchildren know “Waltzing Matilda’ by heart. Last

year an Anzac Day ceremony was held near the town,

with huge press coverage.

I suppose that the American equivalent would be the

landing at Omaha Beach in World War 2.

I am relieved that I have finally established where he

earned the medal, with the additional fillip that he

earned it in an action so famous in Australia.

Later he survived a shell explosion but shrapnel,

which could not be removed, lodged in his neck. More

significantly, during the War he suffered bad shell

shock and amnesia. He spent some time in the UK in

hospital and then returned to Australia on a hospital

ship suffering from “debility”. He spent 2 years

clearing trees for rehabilitation. Later he hated any

noise and had a bad temper (my observations). He

came back a completely different person, by all

accounts.

Nowadays we would diagnose my grandfather and

many other returned soldiers as having Post

Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The purpose of relating some of my grandfather’s

story is to set the scene for a roll call of other people

who served in World War l and are related to readers

of the Jerrems Journal. No doubt readers have had

other accounts passed down to them.

| The “Jerrems” Soldiers |

I have located three members of the Jerrems

family who served in the First World War. They were

two brothers (Henry “Harry” Herbert Jerrems and

William George Jerrems) and their cousin

William

Frank Jerrems. They all lived in Richmond,

Melbourne,

the suburb where their fathers (Robert Cane

Jerrems

and Arthur Reginald) had lived since they had

migrated from Gainsborough with their parents and

siblings in the 1850s.

Harry (1880-1928) was the grandfather and great

grandfather of some of our Melbourne readers

(including Anita Veale and Ian and Ken Jerrems) and

William Frank Jerrems (1885-?) is the grandfather

and great grandfather of some of our Queensland

readers (including Jesse Jerrems).

Harry originally enlisted in July 1915 but was

discharged in March 1916 as being medically unfit

due to back problems incurred before the war.

Undeterred, Harry re-enlisted in January 1917 and

trained for the infantry in England. In due course he

was assigned as a reinforcement to the 38th

Battalion, which he joined in France in January 1918.

He would have seen action in the Battles of Villers

Brettoneux and the Third Battle of the Somme.

Harry’s brother William proved to be elusive, and

therein lies a story. I would not have located him

except that Alexa’s grandmother’s cousin (don’t ask

me to explain where she fits into the family tree!) said

that she met two Jerrems brothers in England who

had served in the First World War. The War Records

did not show two Jerrems brothers, so I checked the

list of men who had enlisted in Richmond and found a

reference to a William George Jerram.

William’s

mother had the same Christian names as Harry’s and

lived at the same address as Harry’s so it was

obvious I had the right person.

William George joined up 5 days after his brother and

in due course trained with the 38th Infantry Battalion in

Cairo (it was probably intended that the battalion

would serve on the Gallipoli Peninsular but that

campaign had finished before they arrived in Cairo).

William was later assigned to the 59th Battalion as a

driver in France (he had described himself as a driver

in his enlistment application). He returned to Australia

in early 1918.

Finally we come to William Frank Jerrems (by the way,

do you remember my article about the number of

descendants named “William”? William George and

William Frank help prove my point). William Frank

joined up on 5th January 1915 (perhaps the result of a

rash New Year’s resolution?) and served at Gallipoli

and France in the 6th Infantry Battalion. He was

wounded in the left hand in August 1918, possibly at

the Somme, and as the result of the wound was

repatriated to Australia shortly before the war ended.

| Other Soldiers |

Relatives of other readers of the Jerrems Journal

served in the War, including Albert Harrison

(the grandfather of reader Brian Harrison) and

Sydney Blamey (Brian’s great uncle).

Albert had served in the Boer War and obtained a

commission when he joined the AIF in 1915, serving

as a Captain in the infantry in France. He was

concussed by a shellburst at the First Battle of Ypres

(a notorious battlefield) and suffered from shell shock.

Sydney Blamey served at Gallipoli and then in the

Camel Corps in Palestine. Finally he was posted to

France where after being awarded the Military Medal

he was gassed and wounded.

A great uncle on my mother’s side (Arnold McDonald)

served all the way through from the Gallipoli landing to

the armistice in the Second Infantry Battalion and (as

related to his son Donald McDonald, my uncle) was

awarded the Belgian Croix de Guerre when he led

about 20 men in capturing a German concrete pillbox

at Passchendale in the Third Battle of Ypres in

October 1917. He was very modest about his

contribution, saying he fired a few shots at the pillbox

with his revolver (sergeants carried revolvers rather

than rifles) and soon after that the German defenders

surrendered. He said he had received the decoration

simply because he was the most senior person there.

One of his men was killed so the operation was

probably not as anti-climactic as he would have had

us believe.

Another great uncle (Cyril Spurge) also survived until

the Armistice. He served as a captain in a Howitzer

Battery at Gallipoli and was then repatriated to

Australia with typhoid fever. A demon for punishment

he returned to the War when he had recovered,

serving in the Artillery from Major to Lieutenant-

Colonel. A note on his record says that he was “Escort

to the King in opening of Parliament on 7th February

1917”. As the end of the war approached he served on

Headquarters staff. He was quite a character, when I

was young he would sit me down on the back steps of

his house and feed me bananas because he said

they were very healthy for small boys.

“JERREMS” MEN IN THE USA

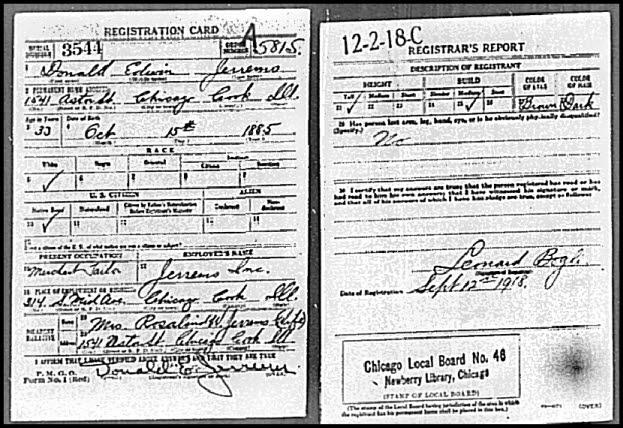

The United States entered the fray in 1917. Two

Jerrems men (Alexander Nicholl Jerrems and

Donald Edwin Jerrems) registered for service but

were not called up.

WHAT ABOUT THE “JERREMS” LADIES?

Recently I came across an interesting piece of

information provided by the British Journal of Nursing.

In April 1918 a number of nursing staff, including

Matron Gertrude Jerrems, were presented to

the King and received awards. As a matron Gertrude

could have been in charge of a hospital’s nursing

staff, most likely a military hospital. So at least one

Jerrems lady served with distinction during the First

World War!

Gertrude was born in 1876 and was a member of one

of the Gainsborough families (she is shown in the

1901 UK Census as living in Gainsborough with her

mother Emma and sister Evelyn).

THE MYTH OF THE TALL BRONZED ANZACS?

This falls into the category of complete trivia, but I

could not help looking at the vital statistics of the men

referred to in this article, as recorded in their

enlistment records.

In the order of mention in this article, my grandfather

was the second tallest, at five foot seven and three

quarter inches (less than 1.7 metres), the three

Jerrems men from Melbourne averaged out at five foot

five inches, Albert Harrison would have

towered over the others at five foot ten and a half

inches, Sydney Blamey was five foot seven inches,

Arnold McDonald was five foot six inches and Cyril

Spurge was about five foot seven inches (no actual

measurement shown).

The photo of my grandfather confirms that the

ANZACS were “bronzed”. But if we take the above

sample of men as being fairly representative then the

figures show that they were on average not tall by our

modern-day standards.

THE LAST POST

Well, I think this article balances the ledger somewhat

for readers who have previously read accounts of the

American Revolutionary War and the American Civil

War. Now we have stories about relatives from Down

Under in a later war.

I would like to hear from other readers who had

relatives who served in the First World War. Sadly, I

would imagine that most readers would not have first

hand accounts like those recounted in this article.

Also, if any of you have been to Villiers Brettoneaux I

would love to hear from you.