Dear Donald,

We continue to look for good Jerrems stories, so please submit them.

We are also looking for an authentic copy of the Jerrems Coat of Arms.

Enjoy.

| Remembering ROBERT COLBROOK |

Ray Jerrems with Research and Recollections by Sandra Walcyk

U.S. Civil War Veteran

Introduction

This article records the information we have located about Robert Colbrook. Readers may remember that he was one of the “Jerrems boys” who served in the American Civil War, as described in the Jerrems Journal of November 2009. Robert was the step son of James Jerrems (born in Wappenham, England in 1812), whose life was outlined in the Jerrems Journal of July 2008.

The main source of information is a fulsome 1906 newspaper report on his death, providing a springboard for a lot of research from Sandra. There were some unusual facets to Robert’s life which I think you will find interesting.

Robert’s birth and childhood

Robert was born in Kent, England on 22nd March, 1841. His parents were Robert Colbrook (1817-49) and Esther (1820-60). He had 2 younger sisters, Sarah Brown (1845-1902) and Harriet Hardcastle (1846-?).

The family migrated to the United States in 1849 and settled in New York State.

After her husband died Robert’s mother married James Jerrems and they had a number of children in New Hartford, near Utica. This marriage meant that James was Robert’s stepfather. Presumably Robert and his sisters lived with James and their mother during their childhood, with Robert shown as being employed as a farm labourer on a farm in the same area in the 1860 Census.

Why did the Jerrems men (including Robert) join up?

It is of course a matter of surmise as to why the Jerrems men joined up to fight for the Union. No doubt there was a strong sense of adventure (particularly in the case of Thomas, who marched out with the first Utica contingent) but there could also have been an element of pragmatism for the other boys, who joined up later. James Jerrems Senior’s farm may not have been large enough to support his sons.

The strong sense of adventure that enticed many Australian youngsters to join up in their mid-teens for the First World War is also evident for the Civil War. We have a case in point with a great great great uncle of Sandra, who enlisted in the Cavalry in 1861 when he was only 15 and died at 16 of “disease” in Washington, D.C. His Civil War record shows he enlisted at age 21, so he must have lied about his age.

I have a friend whose father joined up for the First World War at the age of 15. The books about that War list many similar examples.

Robert’s Civil War service

Initially Robert served in B Company of the 14th New York Volunteer Infantry (this was the same Regiment as the other Jerrems boys joined, but they were in “A” Company) and received a disability discharge on 12 July, 1862 at Washington, D.C. He may have been injured or sick. He presumably re-enlisted after he recovered, a year later, on 28 August 1863 in Company E, 157th Infantry Regiment New York, was transferred into Company F, 54th Infantry Regiment New York on 22 Jun 1865, and was Mustered Out on 14 Apr 1866 at Charleston, SC (after the end of the War).

He probably served in the Army for a total of about three years.

Unlike Thomas Jerrems, James Jerrems and Thomas Mayborn he returned from the war to the Utica area.

After the War-working on the railroad

The newspaper report says that he was a brakeman for the Black River Railroad (Rome-Watertown-Ogdensburg) after the war, turning his back on his earlier farm training. That is probably why we cannot find him on the 1870 or 1880 censuses, because he moved around. This railroad started at Rome, on the Erie Canal, north west of Utica, and carried freight and passengers north, primarily to the industrial city of Watertown (125 km) and then to the city of Ogdensburg (a further 120km) on the St Lawrence River on the Canada border. There were many stations and sidings on the route. At 245 km (160 miles) it was quite a long railway.

Sandra says that the southern portion of the route (Rome to Watertown) would be hilly in spots, whereas Watertown to Ogdensburg would be a flatter terrain. The rail service in winter would probably have been shut down frequently, as the area directly east of Lake Ontario between Rome and Watertown is the “snow belt”, where they receive huge amounts of “Lake Effect” snow (about 300 inches in an average winter).

In the United Kingdom and the United States public railways were built by hundreds of corporations, unlike the position in Australia, where public railways were built far more sparsely by the State governments. The result in the UK and US was a proliferation of branch railways which seemingly ran to towns almost everywhere it was possible for a railway to be built (for instance in Gainsborough, the heartland of the ancestors of one branch of the Jerrems family, the city boasted two railway stations for two different corporations).

Brakeman in action

What was a brakeman?

There is a fascinating historical answer to this question. Although my dictionary says that a brakeman is a person who couples and uncouples railway trucks and carriages, this is the modern role of a brakeman. In Robert’s day the role was spectacularly (and dangerously) different.

In the United States when Robert started work as a brakeman the brakes on the wheels of each carriage and railway truck were operated by a brake wheel placed at one end of the top of the carriage or truck (see photo). The brake wheel turned a long vertical axle which ran down at the end of the vehicle to the wheel brakes.

The brakes on the actual steam engine and the caboose (called the brake van or guard’s van in Australia) at the back of the train were inadequate to significantly slow the train, particularly heavy goods trains, on down-gradients. Additional braking was provided by the brakemen. When the engine driver blew his whistle with a pre-arranged signal the brakemen clambered up from the caboose onto the next vehicle and set off along the top of the swaying train, jumping across the gaps between the vehicles, and energetically turning each of the brake wheels (using a stout piece of wood called a “club” to get extra leverage) so that the brake shoes gripped the wheels. When the train reached the bottom of the gradient the brakemen returned to turn the brake wheels back to the “off” position.

This had to be done day and night (in the latter case by lantern) regardless of the weather. It would have been particularly hazardous in icy conditions. Also, if the train was approaching tunnels the brakeman had to climb down (or lie down if necessary) or face the grim consequences.

If the brakemen were not able to turn enough brakes on in time, or if they mistook the number of vehicles the driver wanted shut down by miscounting (or not being able to hear) the correct number of whistle blasts, the train could run away and possibly be derailed. This was not uncommon. The hapless brakemen could have ended up in the middle of the wreckage, or been injured while bailing out or being thrown off the roof. The thought of being on the roof of a runaway train terrifies me.

The Westinghouse air brake system (patented in 1872) was gradually introduced on new rolling stock, obviating the need for a brakeman to apply the brakes. Instead the driver operated the brakes through a centralized braking system.

Robert was a brakeman for about 23 years, probably (being on a branch line) operating for much of this time under the old manual braking system. He was obviously not afraid of hard work and danger!

Life on the railroad

My initial assumption was that the railroad was probably a hillbilly affair, but in fact it carried freight trains, mixed goods trains and passenger trains. It had a large maintenance depot (including a workshop for building rolling stock) in Rome. It is likely that the train staff stayed with a specific train all the way to its destination, sleeping in their caboose at night (cabooses were much larger than the brake vans in Australia). If this is correct Robert could have been away from home for periods up to five days at a time.

In America individual train gangs stayed together indefinitely. Perhaps this attracted Robert to the job of brakeman because it provided an environment of a close knit group similar to the Army.”

Married life, children

The newspaper report mentions that he had two sons, Robert (Jnr) and Benjamin. They were born in about 1874 and 1876 so their mother was most likely a first wife who we have not located. Robert’s second wife (presumably) was Sarah L. Parsloe (1855-1931) and they were married in 1881. Sarah’s obituary does not mention that she had any children, supporting the conclusion that the mother of Robert Jnr and Benjamin was a previous wife.

The sons were described in the 1906 newspaper article cryptically (and somewhat euphemistically) as having “moved west”. Robert’s continual absences while working on the railroad and his remarriage when the boys were seven and five appear to have had an adverse effect on his sons because they were placed in a Childrens’ Home in Utica.

Robert is injured on the railroad

Life on the railroad went along routinely for Robert for over 20 years until July 1889, when unfortunately Robert (at the age of about 48) was injured when his right hand was caught between the buffers of two railroad cars which he was coupling together in the yard at Holland Patent (see photo) , a little south of Rome.

He had probably started coupling the cars before they had stopped moving, or the engine unexpectedly pushed one of the cars. This injury was no doubt the reason why Robert resigned from his job with the railway, because the injury would have prevented him from carrying out the necessary duties of a brakeman. In the days before accident insurance, workers compensation and social security benefits this would have had a significant financial effect on the family. Also, the 1890s Depression which followed would have adversely affected him.

The newspaper report says that a few years after leaving the employ of the railway he worked at a hotel, and then finally as an elevator man (known in Australia as a lift driver).

Later sightings of Robert

Somewhat strangely Robert appears in 1898 and 1900 in a Home for Disabled Volunteers in the State of Maine. The recordings are strange (but definite) because Maine is a long way from Utica, and he lists his nearest relative as his sister Sarah Brown rather than his wife. Incidentally his height was shown as 5 feet 9 inches (quite tall for those days) and his eyes blue. Possibly there was no comparable hospital in Utica for treatment of his urinary tract problem, or (more likely) the attraction of the Maine hospital was that the treatment was free for veterans. However, things later returned to normal because he was back in Utica by 1904 for an annual veterans reunion.

Reunions of the Fourteenth Regiment Veterans Association

It is obvious that Robert and his fellow veterans were held in high regard. The Utica Herald of 17th April 1904 tells us about the annual reunion of the Association being held in Utica on that day, describing it as “a pleasing gathering of the survivors of that gallant body of fighting patriots. After a meeting the members formed in line and headed by a drum corp the veterans marched to the Munson-Williams Memorial, to give the customary salute to the regimental flags. The program for the occasion included addresses by Mayor Talcotta and Major Miller, the reading of a poem by Comrade Gorton, and the rendering of patriotic musical selections. A banquet will be held in the ????Building this evening”.

Community interests

Robert was described in the newspaper report as being “of a very quiet disposition and one who preferred his home to the current strife of the present day”. However he was not completely the shrinking violet one might expect from this description. He showed an interest in politics, standing on at least 2 occasions (1896 and 1897) as a Republican candidate for the Oneida County Council. He attended the Presbyterian Church and was also an active member of several Masonic Lodges.

Robert dies in 1906

Robert died on 11 Aug 1906 at the age of 65 years at home in Utica.

The Utica newspapers provided detailed accounts of his life and cause of death. The following extract illustrates the role of newspapers in those days (before the advent of radios and television) to keep readers fully informed on essential minutiae:

“Robert Colbrook died at his home while seated at the breakfast table at about 6-45 o’clock this morning. Mr Colbrook arose at 6 o’clock to go to his work at Butterfield House. When he arose he told his wife that he had a severe pain over his heart , but that it would pass away after he went outside. He sat down to breakfast and after taking a drink of coffee he fell back in his chair and died. Doctor Douglas said that his death was due to cardiac asthma.”

Another newspaper added the additional vital piece of information, with great sensitivity, that “Mrs Colbrook, who was in the room adjacent, heard him groan and rushed to his side, but he had breathed his last”.

Perhaps the event could have been called “The Last Breakfast”.

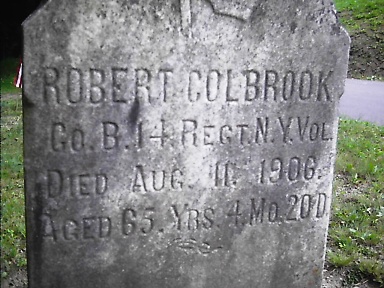

Gravestone, death of second wife

Robert’s gravestone (pictured) is located in the large “Jerrems” plot in the Forest Hill Cemetery at Utica, near the grave of his sister Sarah who died in 1902. His austere gravestone was a standard design provided by the US Government. Robert’s second wife Sarah, who died a long time after him in 1931, is also buried there.

Robert’s children

There is a notable lack of detail about the children in the newspaper article describing Robert’s life and death. There is in fact a very interesting story attached to the children, which I will recount to you in a later Jerrems Journal.

Conclusion

In my opening paragraph I said that there were some unusual facets to Robert’s life which I think you will find interesting.

Do you agree?

Robert’s Gravestone

ÿÿ

| Thanksgiving Greeting |

All the Best to Jerrems families around the World