Dear Donald,

Next month we will send you another Jerrems YouTube.

Stay tuned.

| Easter Island: original song by Egan/Jerrems |

Donald Jerrems

Watch it and Enjoy

From time to time Ray and I surprise ourselves with new Jerrems stories on the WWW. The image to the left is from the YouTube link cited below.

Click on the link to listen to YouTube song with subscriber Doug Jerrems. Doug is Ray’s cousin and a great grandson of Alfred and Susannah Sassall.

Easter Island: an original song by Egan/Jerrems.

Doug’s comment: “This is our first attempt to upload one of our songs. The song touches on environmental issues in the context of the Easter Island experience (tragedy). Vocals – Richard Egan. Harmony – Doug Jerrems. Guitars by Doug Jerrems (Taylor 312CE, Taylor 355CE, Epiphone Les Paul Studio). ”

| THE SASSALL FAMILY STORY (PART 1) |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian

Introduction

This article describes the life and family of my great grandparents Alfred and Susannah Sassall, the parents of Esther Muriel Jerrems (the wife of my grandfather Ernest Alfred Jerrems).

We first met Esther and some of her family (including her father) in an article in the January 2006 Jerrems Journal.

The family grew up in the historic city of Lithgow, a city which was unique in many ways in its physical attributes and in its contribution to the development of NSW from colonial times through to the Second World War. The Sassall family lived in this city to varying degrees over a period of 70 years (ie some left Lithgow, some stayed, and some returned), so I have painted a picture of their lives in this practical context. I think you will like this approach, which I have used in previous articles.

I had previously put the Sassall family in the “too hard” basket because my information on it was fragmented and I had not been able to find anyone to help me sort it out for over five years. Then, lo and behold, a Sassall descendant Graham Harmer (who had googled the Jerrems Journal) contacted me, with his own recollections and a copy of the memoirs of his cousin the late Allan Cargill. Then, would you believe it, Helen Foster (nee Young), another Sassall descendant, contacted me a week later after also googling the Journal. A famine had turned into a feast!

You will see that I have quoted Graham and Allan (rather a luxury). With the volume of information now available I have therefore split the article into two parts.

Alfred “Fred” Sassall

Fred’s father was named George Richard. Fred’s mother Esther died during childbirth and his father died in a colliery accident when Fred was about 10, having remarried. Fred had a younger sister Fanny. According to one account Fred was born in Aberdeen, Scotland (coincidentally Alexander Nicoll (“Nicoll the Tailor”) was born in this area also) on either 31st December 1856 or 1st January 1857. Fred found the confusion over his date of birth very amusing, possibly because he had to admit that he did not even know the year he was born.

After being raised mainly by his late mother’s family he emigrated to Australia at the age of 22. Helen’s research shows that he arrived on the sailing ship “Caroline” at Maryborough, Queensland in October 1878 after a four month voyage from London. He then walked 60 miles to the Gympie goldfields. Jokingly he would relate that he had shovelled most of Queensland BUT found no gold. He then worked setting up the town of Lismore, on the far north coast of NSW. He met up with a friend Cornelius Goodwin from Bloxwich, Staffordshire (where Fred had lived for some time) and they decided to go to Lithgow to find fame and fortune.

Although he was registered as a miner, presumably due to his experience as a miner in Queensland, he was employed for many years in Lithgow as a bread carter. From this he became known as “Fred the baker”.

Fred the baker

Fred worked for a firm of bakers called “Jas. McCall” and, although he was not actually a baker, he was nicknamed “Fred the baker”. Three days each week he did a “bush” run. This was quite a long trip from Lithgow over the mountainous Brown’s Gap and down to the mining town of Hartley Vale, then to Little Hartley at the foot of Victoria Pass, then back down the main western road through Hartley itself, to Bowenfels and then home. This was a distance of about 50 km (30 miles). His cart was a four wheeler with two horses, no doubt two horses being needed for the load of bread (a staple in the diet of people in those days) and the long climbs.

The road (little better than a farm track in those days) over Brown’s Gap was a “short cut” to Hartley Vale, giving expansive views of the sandstone cliffs for which the Blue Mountains are famous.

Fred would have done this picturesque trip in all extremes of weather, starting preparation of the horses and loading of the cart before dawn and finally arriving home at dusk, to rub the horses down and feed them. Miners and other manual workers worked long days and ate prodigious amounts of bread (half a loaf a day of ordinary loaves and a lower proportion of the large high top “cottage loaves”), so it was important that (like the mail) “the bread got through”.

Presumably he delivered bread in Lithgow on the other days.

Perhaps Fred’s longevity (he was ninety when he died) might be attributed to his earlier healthy lifestyle and comparitively safe work environment, particularly compared with working in the Lithgow industries. It was probably also unusual for a Scotsman used to well ordered countryside to embrace the rough Australian conditions. In addition, as you will see, if Fred had not done this baker’s run I would not be sitting here writing this article.

These days the bread is delivered anonymously to the local supermarket, but in those days (and indeed until my post-war childhood days) the arrival of the “baker” and his horse drawn cart was a highly anticipated event in the family’s daily routine. The cheery delivery man was a respected member of the community and had a good grasp of local happenings which he could pass on to customers, particularly those on remote farms on his delivery route.

At the foot of Victoria Pass there was (and still is) a house “Rosedale”, where Fred delivered bread. At this house there was a certain kitchen maid named Susannah Druery, with whom he struck up a friendship. As the result of his calling in three times a week, and possibly a mutual fondness for McCall’s bread and cups of tea, in due course they became engaged. Observant readers will no doubt have guessed that Susannah was my great grandmother, so I will now tell you about her background.

Susannah Druery

I love the name Susannah, it reminds me of that American song “Oh Susannah don’t you weep for me, I’m bound for Louisiana with my banjo on my knee”.

But I digress. This Susannah Druery was the youngest child (of a total of seven children) of Robert Druery, who was a miner in Hartley Vale. She said that she had spent seven of her first thirteen years in and out of sailing ships, from Durham (UK) to Washington State (US) and then to Australia. Susannah, her father and 3 brothers moved to Lithgow, leaving her eldest brother in Newcastle (presumably UK) and two sisters in Seattle.

Nobody has been able to ascertain her exact date of birth. When married she had to have her father’s permission as she was under 21 – date of marriage 20/10/1884. She died on 29/4/51 and her death notice quotes her age as 86, hence she would have been born in 1865 and was 19 at marriage.

After her previous peripatetic existence I would say that Susannah welcomed the opportunity to settle down. But was Fred, the previous wanderer, the man to settle down?

Fred and Susannah marry

The wedding took place in the garden at the Druery residence, in Brewery Road (now Inch Street) on 20th October 1884. Cornelius Goodwin was Fred’s best man and no doubt the bride looked radiant (they always do!).

Fred and Susannah settled into a house in the same street and proceeded to produce numerous children, as people did in those days. Briefly they were Esther Muriel (my grandmother) b1885, Clara Maude b1886, George Robert b1888, Alfred Enoch b1890, Mabel (May) Constance b1892, Amy Agnes b1897, Lucy Gladys b1898, Baden Powell b1900, Allan Warren b1904, Ethel Audrey b1909.

In addition to raising her own family, for some time Susannah also raised the three children of her widowed older brother Thomas G. Druery. Thomas arrived in Sydney in 1877 and married an Edna ?? who died in 1888, when her youngest son Fred was then two years old.

Alfred’s personality

In the family photograph above we see (from left to right) my grandmother Esther, Fred (aged about 37) holding George, Clara, Susannah holding May on her knee, and Alfred Jnr. Fred is smartly dressed with tie, waistcoat and spotless white shirt, his hair is carefully parted, and he has a large moustache and broad shoulders. Perhaps he looks as though he would have preferred to be somewhere else.

Grahan Harmer (who was nine when Fred died) tells us about Fred when Fred was in his eighties:

“My own memories of Grandfather Fred are of an old man sitting at the end of their baize covered dining room table at 10 Macdonald Street Ramsgate (in Sydney) reading Braille books of about A3 size some 80 or so mm thick wearing a smoking cap of the type shown in the Jerrems on-line photo. As might be expected being blind, he had an acute sense of hearing and you could not come anywhere near without him being aware of your presence. ”

“Apart from Susannah’s cooking, he put his longevity down to regular morning gargles with a salt water solution – something he did with gusto and volume. My own father got on well with him as a fellow churchman and Freemason – also having a keen sense of humour too ! Remarkably both Fred and Susannah visited us (travelling by train) at both Llangothlin and Sodwalls railway houses.

“We have a delightful photo of Fred sitting in the sun shelling peas in the backyard at Llangothlin while we have a family Christmas photo taken on the verandah at Sodwalls which also includes Aunts Amy and Luce in 1947. Fred was close to 90 and Susannah close to 80 at this time.

Fred was well educated despite his modest occupations, possibly reflecting his mixed fortunes as a teenager after his father died (he was probably not able to do a trade). A keen Scottish Presbyterian he played the organ at church. When he became blind he taught Braille for the Industrial Blind Institute.

Susannah’s personality

In the group photograph Susannah (aged about 29) looks serious, her hair is pulled back, and she is wearing a pretty high-collared dress.

Perhaps the best and most touching tribute comes from Susannah’s late nephew Fred, who she took in when he was two, writing to May Pillans (nee Sassall) in 1973 as an 88 year old. Fred wrote in part

“The Sassalls, parents and family, have been very dear to me since I was a little child. Aunt Susie was wonderfully kind, capable and loving. Very early in childhood I learned that when my dear mother passed away, Aunt Susie cared for me for a considerable time when my sister Agnes, a brave and useful girl of 13 years took me home and mothered me. I shall be ever grateful for the services of others in my early childhood”. Fred later trained for the Presbyterian ministry in 1936, serving at Tumbarumba, Coolamon and Taralga-Crookwell among other locations.

Again Graham Harmer helps us out also (he was 13 when Susannah died):

“If anyone could portray a stereotypical Grandma it was Susannah. She was a fastidiously clean and well organised housekeeper but also a very warm ‘mother hen’ type of woman always with time to give her grandchildren on whom she showed warmth and genuine affection. To her siblings and other adults she seemed to me as a young boy, to be an upright, rather strait laced person of obvious integrity to whom all other adults seemed to defer in her company. She most certainly taught my mother to knit, sew, embroider as well as cook with economy and skill. The affection nephew Fred showed in his letter above about her perhaps well encapsulates the attitude of most towards her. It greatly distressed me to see her slide into dementia before her death”.

The origin of the group photo

This is a fascinating story. It was sent to me by Graham Harmer. Fred and Susannah’s youngest daughter Audrey (Graham’s mother) used to keep regular contact with a cousin who was a descendant of Susannah’s sister Annie, who lived in Seattle. When Audrey died her daughter Ruth kept up this contact and in 1996 the cousin sent Ruth the photo of the Sassall family taken at the side of their house in Brewery Road (later named Inch Street) in 1894. This was a remarkable find given that the original photograph must have been sent to America a century earlier.

The photo shows (from left to right) my grandmother Esther, Fred holding George, Clara, Susannah with May on her knee, and Alfred Jnr.

When I look at the photo I feel quite emotional. I think to myself “These are the great grandparents I have heard about for so long, yet they look so young. And they had five more children after the ones shown in the photo!”

It is now time to look at the environment in which Fred and Susannah lived, in Lithgow, to obtain an idea of the challenges they faced.

1905

1905

photo Fred is on the left

Lithgow

(a) Location

Lithgow is situated in a valley below the western scarp of the Blue Mountains, 150 km west of Sydney. The valley, with its surrounding sandstone cliffs, is picturesque. Until the railway was built from Sydney Lithgow was in a comparative backwater. Coal had been found there in 1838 and was used for local consumption, but all this changed when the railway came through the town in 1869. Lithgow supplied coal to the rapidly expanding railway system and iron production was commenced there. It became a commercial centre which supplied goods and services to its expanding population, the adjacent rural areas and the railway towns to the west.

(b) Collieries

Collieries were opened along the sides of the valley at the foot of the scarp, where a huge coal seam was accessible. These collieries ran tunnels almost horizontally into the seam, enabling the coal to be brought out by trolleys in large quantities, in contrast to the types of mines where vertical shafts were dug and material (typically ore) had to be lifted out vertically.

These collieries, located in Lithgow (including the adjacent areas of Oakey Park and the Vale of Clwydd) included the Zig Zag Colliery which opened in 1873 and closed 60 years later in 1932.

Collieries tended to be opened to supply specific iron and steel works, one exception being the Zig Zag Colliery, where Thomas Sutcliffe Mort mined coal to supply his meat and freezing works which he had established at Morts Estate, Lithgow. The meat was forwarded to Sydney in a frozen condition in specially built rail trucks. The other notable exception was the State Mine which supplied the railways, railway workshops in Lithgow and power generation.

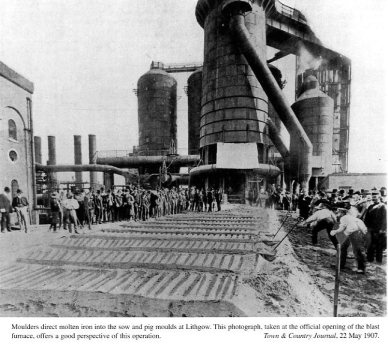

(c) Increases in iron and steel production The rate of iron and steel production gradually increased, due to technological advances (such as the invention of the Bessemer Converter which enabled steel to be produced directly from the raw components) and increased railway demand (caused by the 1875-90 extension of the railway system to Bourke, Mudgee and from Blayney to the Southern line, and subsequent extensions). This increase in production is illustrated by the opening of the huge Hoskins blast furnace in September 1908, within sight of Fred and Susannah’s home.

This blast furnace dramatically changed the Lithgow landscape with its huge buildings and smoke plumes, and it lit up the nightscape with its pyrotechnic displays as the furnaces were opened.

Travellers at night on the Zig Zag Railway, which overlooked the valley, often talked about “the wondrous view of a ‘sea of fire’ below”. My father described the eerie nights when the flames from the blast furnaces lit the sky and there was the incessant clattering of steelworks machinery which operated around the clock. Small steam engines ran busily out to the end of the slag heaps pushing truckloads of glowing red-hot slag which were tipped over the end of the slag embankment. The slag glowed for days, adding to the “sea of fire”.

A short time later (1912) the Lithgow Small Arms Factory (SAF) was opened and tooled up to produce Lee Enfield rifles, soon produced by the hundreds of thousands for the First World War.

(d) Air pollutionThe downside of this visually spectacular industrial activity was that the polluted air was often trapped in the valley by clouds or inversion layers, causing great anguish to some of the inhabitants, particularly my grandmother who suffered from asthma all her life. The Sassall women were meticulous housekeepers, they would have had a continual battle with the grime resulting from the fallout of dust. They had to wipe the clotheslines before they could hang out the clothes, and if the wind swung to the south they had to rush out and bring in the washing, to save it from being covered in soot from the smoke of the double-heading steam engines labouring up the nearby Esk Bank towards the Zig Zag.

Although their contribution to pollution may not have been high compared to the industries and railways, townsfolk contributed by using coal (supplied free to the miners’ families) and wood in their house fires

The climate of Lithgow was also challenging, ranging from snow in winter to heatwaves in summer. During the big bushfire season of 1905, with flames ringing the mountains, in a nearby area a thermometer carried in a train on New Year’s Eve registered 127 degrees!

In 1910 the “Zig Zags” were removed from the railway line from Sydney, increasing the speed of travel and the volume of goods which could be carried to and from Sydney. Lithgow became a centre for administration of the railway. It was said that the railway workshops were so extensive in later years that a steam engine could have been built there.

It was against this backdrop that Alfred’s numerous family grew up.

The Sassall’s house

Houses in those days were built with a very simple design which minimised cost and which tradesmen could construct with minimal supervision. The houses of Jerrems families in Melbourne were of similar design.

Graham observes that:

“From what my mother told me, the Inch Street house was very like the first railway house she lived in at Llangothlin – of timber weatherboards with corrugated iron roof. There was a verandah right across the front of the house with a centrally placed front door which led into a central corridor off which four rooms (2 on each side) of approx the same size opened. At the back of the house was a separate kitchen, laundry and pantry/storeroom. Essentially it was basic working man’s cottage. I cannot advise if it still exists. I have seen it listed as both 42 and 49 in family documents. Using Google Earth, 49 (on the Blast Furnace side of the street) now seems to be a factory/storage type building. Incidentally Inch St. was apparently named after a pioneer of the district.”

Inch Street (formerly Brewery Road, probably because it led to the Zig Zag Brewery) ran for several kilometres in a loop configuration around the large area of land (probably a grassy common originally) finally used for industrial purposes. The family therefore had a bird’s eye view of the growth of the iron and steelmaking industry, which had started very modestly before they first moved into the house but in later decades dominated the landscape.

My Aunty Vi said that the slag heap came almost up to the back fence of the house. If the engine driver was too enthusiastic the slag ran down the embankment to the house’s back fence and burnt it down. Slag took a long time to cool down, and its appearance could be deceptive. On one occasion a young Aunty Vi and her companion were playing in water and were soaking wet. They took off some of their clothes and placed them on some slag to dry in the sun. When they returned the clothes were burnt to a cinder, demonstrating the amount of heat retained by the slag. Very embarrassing for young girls.

Graham adds that his mother Audrey would certainly have agreed with this as she told Graham that Father Fred was in a constant battle with Hoskins to keep his back fence unburnt or replaced when it was!

George dies in blast furnace accident

George Robert Sassall (the little fellow standing in front of his father in the group photo) married Elsie May Durie (not to be confused with “Druery”) in May 1912. In December, at the early age of 24, he was killed in a blast furnace accident. Industrial accidents were frequent in those days, but this accident was particularly tragic, George and Elsie had only been married for seven months and 21 year old Elsie was expecting their first baby.

George’s accident was freakish. Working in Hoskins blast furnace area, a painter had been hoisted up in a sling called a bosun’s chair, and the partly burnt rope supporting the sling broke. The painter landed on top of George, who was laying bricks below him. The coroner said that George’s neck appeared to have been broken, so he would probably have died instantly. Elsie sued the company but was unsuccessful, presumably incurring legal costs which she could ill afford.

Graham’s mother Audrey told him that as a little girl her dominant memory of George was that he was “laid out” in one of the front rooms of the house with pennies on his eyelids to keep them shut before he was taken away for burial.

The community would have rallied around young Elsie, with her husband’s parents and nine siblings, and her own parents and (coincidentally) her own nine siblings at the forefront. These people and their own families, George’s workmates, and all their friends would have attended George’s very sad funeral, and no doubt the hat would have been “passed around” for contributions to help young Elsie.

As happened in those days, Elsie would have been supported by her huge extended family, but this would not have taken away her loss.

For Elsie’s family, in particular, there must have been a poignantly familiar ring to this situation. The Duries had lived in the nearby coalmining town in Hartley, where their son Frederick (who married Clara Sassall) was born in 1883, and later (in 1891 when Elsie was born) they lived near the coalmining town of Wallsend. Mining accidents were common, and the risk of death or injury hung like a cloud over the mining communities. No doubt the coalmining accidents at Bulli in 1887 (where 81 people were killed) and at Mount Kembla 1883 (the worst mining accident in Australia’s history where 96 people were killed) would have still been in the memories of Elsie’s parents. Closer in family terms was the fact that Fred’s father had been killed in a colliery accident in the 1860s.

When George Robert Sassall (Jnr) was born soon after in January 1913 the celebrations would have been tinged with sadness that his father was not there to join in the celebrations.

The high incidence of deaths and injuries in those times

The mining tragedies at Bulli and Mount Kembla were only the tip of the proverbial iceberg. In the days before Government supervision of working conditions (known in Australia as “Occupational Health and Safety”) fatalities and injuries in all industries were frequent. Also, medical knowledge was poor. A case in point was related to me by my mother-in-law Nancy, who was born in 1912 in the famous Victorian goldmining town of Ballarat. Four of her uncles were goldminers, and three of them died before they were 40 from lung diseases caused by the dust in the mines, leaving families behind. This was also common in places like Lithgow and, according to my grandmother, extended to the firemen who shovelled the dusty coal on the steam trains.

Watch out for Part 2 of the Sassall Family Story

I promise that the next Part of this story will not be so serious. It will have some humorous stories.

Hoskins blast furnace 1907

| Administrivia |

Donald Jerrems

New Subscriber

We welcome new subscriber, Graham Harmer(a grandson of Alfred and Susannah) from Kiama, NSW.