Dear Donald,

Another milestone edition for the Jerrems Journal: #75

This edition is just a few hours late past out usual end of month

deadline for those west of the International dateline.

| VILLERS BRETONNEAUX AND LE HAMEL |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian

Introduction

This article follows on from the article in the Jerrems Journal of February 2009 about Jerrems men and relatives who served in the First World War.

In that article I spent a little time talking about Villers Bretonneux, a small town in France where the feats of the Australian troops in April 1918 (described in this article) in liberating the town are still recognised by the townspeople. Later in this article I also describe the Battle of Le Hamel where Americans took part with Australians for the first time.

Villers Bretonneux

In recent years Villers Bretonneux has gained a popularity with Australian tourists rivalling Gallipoli, and the Anzac day dawn service at the Memorial north of the town is very well patronised. A number of Journal readers have visited it, and it has a particular connection to the Jerrems relatives because my grandfather served there (and was awarded the Military Medal there) and another relative is buried there.

Famously for Australian visitors, the school and the town’s community hall have displayed a sign that has become legendary in Australia: “Do Not Forget Australia”. Also indicative are a “Melbourne Street” and an “Aussie Cafe” in the town.

Villers Brettoneaux is 16 km east of Amiens on the road to St Quentin (Amiens is 133 km due north of Paris).

Annual Dawn Service on Anzac Day

The Villers Bretonneux Military Cemetery was established in the early 1920s, and in 1938 King George VI opened a memorial in the grounds of the Cemetery to commemorate all Australian soldiers who fought in France and Belgium during the First World War.

For the last three years there has been a Dawn Service on 25th April (the day that Australians celebrate “Anzac Day”) at the Memorial. Previously the only major overseas annual Anzac service has been held at Gallipoli, where about 8,000 Australian visitors assembled this year.

The Villers Bretonneux Dawn Service last year was attended by about 3,500 people waiting patiently for daybreak in freezing temperatures, with only a slightly smaller number this year despite the current economic downturn. Most of the people who attended were Australians, supplemented by the townspeople, with Australian and French dignitaries (including the Town Mayor) in the official party.

Many of the visitors at the Gallipoli and Villers Bretonneux services are young Australians whose relatives, perhaps great grandfathers or great great uncles, served (and possibly died) in the First World War.

But what actually was the Battle of Villers Bretonneux?

The Battle of Villers Bretonneux

In military terms it must be said that the actual battle was not a major operation, being small by American Civil War and First World War standards. However the result was excellent for the morale of allied troops in the Western Front campaign, and for the Australian public which had been reeling for several years under the casualty figures published daily in the newspapers.

The Battle followed a strong push by German troops, who had captured the town some days earlier. The Germans had not penetrated this far west before. An alarmed Allied Army Command threw a strong British force into a traditional frontal attack on the town, which was repelled largely because the Germans were expecting such an attack. The Allied Command’s next step was to call on the Australian troops to step in at very short notice to retrieve the situation.

Briefly, in a surprise decision the Australian Command chose two simultaneous attacks around the north and south of the town, joining up behind the town and successfully attacking the town’s German defenders from the rear and the sides. This was completely contrary to the grinding frontal campaigns favoured by the British and French commanders.

A significant aspect of the plan was that the areas outside the town (unlike nearly all the other areas to the east and north) had not been fought over before. The result was that the area was devoid of trenches for either side, except for some shallow trenches dug by the Germans in previous days, and there were obviously no fortifications like concrete pillboxes (German pillboxes had concrete up to two feet thick and harboured machine gun nests). This meant that the Australian troops could move quickly. Conversely there was very little cover so the Australians had to attack over open ground.

The Australian troops started out at 10 o’clock at night after a short “softening up” bombardment of the German positions. Initially the attack caught the defenders by surprise because bombardments usually lasted much longer, giving the enemy time to prepare. Also attacks were normally preceded by barrage balloons and aircraft plotting the land and enemy defences for days.

Instead the Australians had to “wing it”. When the Germans realised what was happening they opened fire with their machine guns (raking the areas at a withering 600 rounds per minute) by the light of flare shells. Despite high Australian casualties rates comparable with those of earlier battles (over one third of the men were killed or wounded) at least the operation was successful.

The Jerrems relatives connection-William James Blamey

I did not mention William in my previous February 2009 article for the simple reason that I had not heard of him at that stage. His connection with Villers Bretonneux is that he is buried there in the Australian Military Cemetery in Plot III. C. 8, so this is an ideal time to tell you about him.

William was the great uncle of JJ reader Brian Harrison, being Brian’s maternal grandmother’s brother. His grandmother was Norah Harrison.

Born in Cornwall, William migrated to Australia and later enlisted at the age of 39 in June 1916 while working as a miner at Mt Morgan in Queensland. He went to France as a reinforcement for the 11th Machine Gun Company. After being transferred to the Third Machine Gun Battalion as a Vickers gunner he was wounded, gassed by a gas shell and suffered from shell shock. After he recovered from this in hospital, a month later (on 4th July 1918) he was killed by shellfire in the Battle of Le Hamel (also called Hamel). This was a very successful attack by the Australians, who suffered much lower casualties than usual, so one might say that he was particularly unlucky to be killed. Initially he was buried in the Le Hamel area but later his grave was relocated to Villers Bretonneux.

It is possible that William was earmarked for machine gun duty because he was fairly big in build for those days (5 foot 8 inches and over 11 stone) and had been a miner. These were ideal attributes for a Vickers gunner because (depending on the number of attachments) the gun itself weighed 25-30 pounds (11-13 kg), the stand weighed 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg) and an ammunition box holding 250 bullets on a belt (a 30 second supply) weighed 22 pounds (10kg). These had to be carried over broken ground as fast as possible to set the weapons up and replenish the ammunition.

Machine gun battalions (formed in 1918) had a strength of about 50 officers and 870 other ranks, equipped with 64 Vickers machine guns. My mathematics indicates that for each gun there were at least 13 men, two of whom carried the gun and stand and the rest presumably relayed the boxes of ammunition.

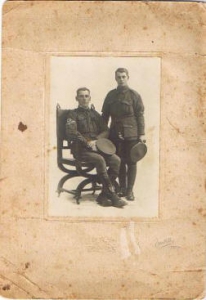

Above is a photograph of his original grave.

William was one of 4 brothers, three of whom enlisted. One of the other 2 brothers who enlisted was killed at Gallipoli, and the other died tragically after the War, probably the result of his wartime experiences.

In a sense Norah was a casualty of the War. Her husband did not return to Australia, under somewhat mysterious circumstances, so she effectively lost her husband and 3 of her 4 brothers due to the War. Courageously she raised 4 boys in Sydney, Australia by herself, with some financial assistance from her only surviving brother (who lived in Melbourne) and possible assistance from a sister.

The Americans help in the Battle of Le Hamel, 4th July 1918

This Battle has (like the Battle of Villers Bretonneux) earned a place in the annals of Australian folklore.

Le Hamel was a strongly fortified key German defence position which protected the area between Villers Bretonneux and the Somme River to the north. Although small in scale, the battle was one of the most important undertaken by the Australians on the Western Front. It tested new offensive techniques, including the co-operation of infantry, artillery, tanks (60 huge Mark Vs) and aircraft which were used a month later on a much larger scale which led to the Allied victory in November 1918.

The battle lasted just 93 minutes. The Australian Commander of the operation, Lieutenant-General John Monash, estimated that the battle would last 90 minutes, but he was a little optimistic, it lasted 93 minutes. Unfortunately for William Blamey, this was 93 minutes too long.

Interestingly, this was the first time Australian and US troops fought together in this War. The ten companies of the 33rd American National Guard Division under the command of Pershing had been training with the Australian Corps for several weeks and four American companies went into the battle. About 7500 Australians fought in the battle, Australia and the United States suffering a comparatively low total of 1400 casualties.

The Australians got on well with the Americans, who had a bit of the “larrikin” in them, like the Australians.

Although this American force was modest in size, in the following months the Americans contributed several Divisions to help the Australians. It should be borne in mind that the bulk of the American forces (a gigantic total of 2 million Americans served in France, from 1917) had been operating further south assisting in the major British and French campaigns. This, combined with the enormous supply of equipment provided to the allies by America, had a very significant effect on the course of the War.

The second Jerrems connection -my grandfather

Coming back to the Battle of Villers Bretonneux, my grandfather (Edward Smith) was a stretcher bearer in the 13th Field Ambulance. He was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry occurring on the 21st April (when the night attack commenced) so he must have been just behind the first wave of Australia infantry attacking along the northern side of the town. The stretcher bearers would have had no shelter from natural features or from the usual shell holes and remains of old trenches left over from previous battles, so they would have risked being hit by the machine gun fire aimed at the Australian troops ahead of them, while attempting to tend the casualties out in the open.

My grandfather told me that his companions refused to move from a shelter they had found, waiting for the fighting to move further on, out of machine gun range. But he went out by himself simply because the cries of the wounded “would have sent me mad if I had stayed behind”, he said. Probably wearing a great coat in the cold, he said that he later found bullet holes in his clothes!

The Last Post

I hope you have found this article to be informative. Incidentally I would be surprised if any UK or US readers had ever heard of the Battles of Villers Bretonneux or Le Hamel before reading about them in the Jerrems Journal.

In the broad scale of the war on the Western Front they were not a big deal, but (as I said earlier) they have become part of Australian folklore.

My grandfather (Edward Smith) and his brother