Dear Donald,

mountaineer hiker several decades ago. <br><br>

The mountain range west of Nowra, which is on the coast about 100

miles south of Sydney was officially named (by the NSW Geographical

Names Board) “Jerrems Spur”, a side ridge which runs from the range

down to Bunbundah Creek. The spur was named for Ray. (JerremsJournal

July 1965).

With this edition Ray takes us back for a sentimental journey to the

mountains .

| Introduction |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian, and Mountain Adventurer

The Snowy Mountains (in the south of New South Wales) and the Main Range to the north originally contained about 120 huts that were built by stockmen, miners, fishermen, skiers, the Snowy Mountains Authority and others. The huts provide interesting destinations for bushwalking or ski trips, as well as life-saving refuges in bad weather. Their various designs, materials, construction methods and locations are particularly interesting.

To step into one of these huts is to take a giant step back in time. I have very happy memories of some of them from my bushwalking and cross country skiing trips in the 1960s. The emphasis of their builders was definitely on functionality rather than good looks, as you will see.

Many of the mountain huts have disappeared over time through neglect or bush-fires but the ones that remain are preserved and maintained by the Kosciusko Huts Association and other volunteer organizations.

| The high country |

I have used this generic term to cover the Main Range from Kiandra 60 miles south to Australia’s highest mountain (Mt Kosciuszko) at 2228 metres/7310 feet, using the intermediate Mt Jagungal (2061metres/7310 feet) and Mt Gungartan (of a similar height) as reference points.

Mt Jagungal and the range from Gungartan to Kosciuszko are above the tree line due to their altitude, affording open skiing and bush walking but making navigation difficult in adverse conditions which can develop very quickly.

The aerial photo at the top of this article shows the Mount Kosciuszko area swathed in snow, with sharp drops down to the tree line.

The following is a sample of the huts, selected due to their method of construction, their location or their nostalgia value to me. They remind me of the Clint Eastwood western “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”.

| Wheelers Hut |

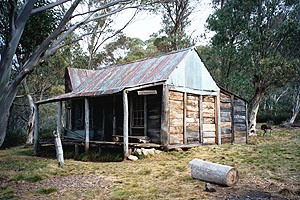

This hut provides the biggest step back in time. Located to the north of Mt Jagungal a fair way below the tree line it was built in the early 1900s (making it over one hundred years old) using methods of construction widely used previously in the 19th century on the gold diggings and early pastoral holdings. It is probably typical of even earlier construction in the colonial days. As such it gives unique insights into the use of “slabs” to construct the legendary slab huts. It is one of only four surviving huts where slabs were used.

The owners, together with many other hut owners, ran sheep and cattle on these high plains in summer from the early 1900s to the 1960s using what became known later as “snow leases”, a big attraction being that the areas were rarely affected by drought. The stock were taken out to the low country for winter. The leases were terminated in the 1960s and the lands were included in the new Kosciuszko National Park.

Initially alpine ash trees (a sample log is conveniently situated in the picture) located in the area were felled and “slabs’ were split from them lengthways using sledgehammers and a row of wedges. In this case the slabs are horizontal and neatly fitted between sturdy uprights placed at intervals of about a metre. Each upright is precisely mortised (recessed) into the top and bottom plates (beams) and a wooden peg holds the plates at the ends where they join the corner posts. There are five panels of slabs across the ends of the hut and seven panels along the front.

Slabs have been laid flat to form the verandah and inside floor of the hut and smoothed with a long-handled adze, shaped like a sharp-bladed mattock.

Readers from the northern hemisphere, where softwood pines predominate, may wonder why so much time and effort was spent on obtaining slabs. The answer is quite simply that the Australian hardwoods are so tough that it is far easier to split the logs than saw them lengthways (probably also requiring the construction of a sawpit). The logs do not split in straight lines for far, so short one metre lengths are the optimum length for hut construction. Bushmen were well versed in splitting logs because these tools were also used for the construction of stockyards and post and rail fences.

The hardwood timber had the advantage that it was very durable.

In other respects the hut has an orthodox corrugated iron roof, the iron probably having been brought in by packhorse. It is possible that it originally had a bark roof.

| Four Mile Hut |

This provides a step forward, to demonstrate the use of vertical slabs. Built near Kiandra by a gold miner at the northern end of the high plains in 1937, this hut has an interesting mixture of techniques. It has vertical slabs on the left, split planks below the window, and flattened four gallon kerosene tins have been used for repairs to the left of the window. It also has a large chimney, used on many of the huts.

One attribute of a large chimney is that if the hut is covered with snow access can be obtained by climbing down the chimney. In fact in the tiny Cootapatamba Hut, on the lake of that name below Mt Kosciuszko, the only means of access was via the chimney, rungs having been placed on the outside of the chimney to enable people to climb up to the top.

Another attribute of a large chimney was that it accompanied a huge fireplace which a number of users could sit directly in front of, and when the fire had died down wet clothes could be hung up in the chimney to dry.

| Tin Hut |

This hut provides a slight step back in time, but the purpose of construction was different. This small hut was built at the top of the tree line in a very windy location in 1926 (making it a mere 86 years old) for the first Kiandra to Kosciuszko ski crossing. With financial contribution from the Tourist Bureau it was the first hut built for ski touring. It was constructed from corrugated iron and timber brought in by horseback. When I visited it in the 1960s it had only three or four beds, but it was wonderfully snug, emphasised by the whistling of the wind outside.

Perched at the top of the tree line on the eastern side of Mt Gungartan it was difficult to find because the mountain was flat on the top and there were no navigational features. We used a compass bearing from the trig station until we found some old marker poles which one of our party remembered from an earlier trip. This was a typical problem and emphasised the need for at least one person to be familiar with the location of the huts so that they could be found in bad weather, or when it was snowing, or at night if the party was delayed.

Even worse, the most extreme condition is a “white out”in snow conditions where visibility is reduced to almost zero (on one occasion I could not see the tips of my skis).

| Seaman’s Hut |

Built several years after Tin Hut, this hut was built for another purpose again. It is a refuge hut some distance above the tree line. The birth of this hut, below Mt Kosciuszko, was the result of a winter tragedy in 1928 when Laurie Seaman and his companion lost their lives nearby in blizzard conditions. This tragedy, where the body of Seaman’s companion was not found for several years (they had become separated) demonstrated the unforgiving nature of the high country. It could be beautiful and it could be deadly.

Financed by Seaman’s parents and built by the Government the following year, it was constructed from granite. Needless to say, this is the only hut with this massive method of construction. With two rooms and a storeroom it can hold quite a lot of people, and being on the road to the Kosciuszko Summit is the only hut in the area which can be easily located.

This hut is also the highest on the range, a long way above the tree line. This makes it attractive for cross country skiers. As spring progresses and the snow melts in the valleys there is still a lot of snow on the tops. I remember skiing to the hut in November 1970 and that night skiing by moonlight to the summit.

| Mawsons Hut |

This fairly large two roomed hut (plus store and firewood room) was built by graziers the following year, 1930. Located to the south of Mt Jagungal, despite its barn-like appearance (its windows were on the hidden side) it was popular in later years for bushwalkers and cross country skiers wishing to climb Mt Jagungal. One of the bedrooms had a large fireplace, like most of the huts, and a collection of books on the mantel piece included three volumes of the collected works of the poet Banjo Paterson. After a day’s skiing or bushwalking (depending on the season) I loved to curl up on the bunk near the fire and read the poems by candlelight, fortified by a mug of red wine.

Contrary to folklore, it was not used by Mawson’s Antarctic expedition in the early 1900s for training.

Unlike most huts, it had an outside “dunny” about 30 metres away, a small tin shed housing a “long drop”. In winter the shed could fill with snow and had to be cleared out with a shovel. On a snowy night one had to allow time to clear the snow.

This hut was located below the tree line in a stand of trees and could be difficult to locate for people navigating off the flat topped high range (The Kerries) to the south. Sadly, two young bushwalkers lost their lives in 1971 the night after I had set out from the hut for Mt Kosciuszko. It was snowing heavily in an unusually early autumn “dump” of snow and they had been caught in the dark before they could find the hut. Their bodies were found the next morning only 50 metres from the hut. Meanwhile I had reached Seaman’s Hut and woke up in the morning to find two feet of snow outside.

| Pretty Plain Hut |

This hut was built five years later, in 1935, well below the tree line. Located west of Mount Jagungal, this was reputed to be the largest and coldest (draughtiest) hut in the mountains. It was built by the owner of Khancoban Station (Captain Colin Chisolm) and destroyed by fire in January2003, although a new building has now been built. It was one of only four log huts in the high country, due no doubt to the difficulty of finding straight logs in the area (the logs were brought in from lower down by three bullock teams).

Northern hemisphere readers will see that it was built along the lines of the Northern Hemisphere huts made from pine trees. Of particular interest is the technique of interlocking the logs on the corners of the building and the lower part of the chimney.

| Acknowledgements |

This article has been compiled from my experiences and information from the book “Huts of the High Country”, published in 1982 by Klaus Hueneke. Most of the photos came from the website: http://members.pcug.org.au/~alanlevy/KosciHuts.htm.

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed this article, which is a little unusual compared with most of the articles I have written. I have very fond memories of the mountain huts. In a later article I will talk about how the mountain huts were equipped and the lives of the stockmen and skiers, with some anecdotes thrown in for good measure.