|

in this issue

— Jesse Jerrems – Longboard Champion (By Ray)

— It’s a GIRL! (Jerrems Population Grows)

— New Subscribers

— Jerrems History (By Our Chief Genealogist)

— Letters to the Editor

Dear Donald, Hello cousins….Thanks to those who have contributed to the Journal articles and referrals. Our circulation is up, expecially in the southern hemisphere. Our intrepid Roving Reporter, Ray, has a couple of featured articles. |

Jesse Jerrems – Longboard Champion (By Ray) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

For the benefit of our US readers, Noosa Heads would have a similar climate to Florida, minus the hurricanes. Jesse is the first reader to enlist from his arm of the Jerrems family. In an enthusiastic email to Ray he referred to his recent win in the Queensland Longboard Championships (a “longboard” used to be called a surfboard) completed on 11 July. The top surfing magazine “Australian Surfer” carried the following report: “Facing gusty offshore winds and trying conditions at Sunshine Coast’s Coolum Beach today, Queensland’s premier longboarders battled hard for prestigious Queensland Titles on the final day of the Bradnam’s Queensland Longboard Titles. Longboarders from 15 to 60 years of age showcased their finely tuned styles in front of today’s large crowd. Sunshine Coast surfers dominated today’s proceedings, securing 8 Queensland Titles out of 12 divisions as well as gaining 19 places in the illustrious Golden Breed Queensland Longboard team to compete at this year’s Golden Breed Australian Longboard Titles on the Sunshine Coast in early October. “In the blue ribbon Open Men’s division, Noosa Head’s Jesse Jerrems out-surfed fellow Sunshine Coast surfers – Damien Coulter, Trent Dickey and Curtis Portingale, to secure victory and win his first Queensland Open Men’s title. In a wave starved heat, Jerrems scored a total of 11.26 points, beating Coulter’s efforts, a combined two wave score of 10.36. At the proceeding presentation, Jerrems dedicated his win to his late brother, savouring the moment with an emotional speech.” The reference to Jesse’s late brother was a reference to Liam, a remarkable young man who we will write about in a later Journal. Jesse has followed in the footsteps of his father Rob, also a keen board rider. Jesse has competed in Australia and overseas, including New Zealand, where he also won a competition earlier this year. Congratulations Jesse! By the way, if you think that the name “Jesse Jerrems” is unique, a Jesse Jerrems from Utica in New York State served in the American Civil War in the 1860s. Unfortunately he was killed in that War, with a brother. A third brother survived (this arm of the family has died out, at least as regards the male line). This family will be described in more detail in a later Journal. |

It’s a GIRL! (Jerrems Population Grows) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jess was born on Friday 29th July at 5.18 am (one must be precise about such things!) and weighed 7 lb 1 oz. Her mother is Anita McDonnell (nee Jerrems) and her father is Bradley (“Brad”). Brad’s parents, John and Anne (who live in Auckland but come from Sydney) were close at hand. Jess is the first grandchild for the grandparents. Di and Ray arrived in Auckland on the following afternoon to find Jess and Anita to be in good health. Neither Ray nor Di could believe how tiny she was. Jess can be contacted at Jessmcdonnell@yahoo.com between feeding hours. She plans to be christened in Sydney in October and will arrange for family photos to be sent to the Journal Editor. She has also arranged for her great grandparents (Syd, Margaret, Thelma and Nancy) to be at the christening. |

New Subscribers ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A warm welcome to new Melbourne recruits Lance, his wife Linda, and Ken Jerrems. Lance and Ken were Carol’s brothers (see below) and are the first people to sign up from their arm of the family (all arms are now represented as subscribers to the Jerrems Journal). Welcome also to Ari, from Canberra. Ari’s father (Doug) originally supplied a lot of very helpful googled material to Ray. |

Jerrems History (By Our Chief Genealogist) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ray has received a number of requests from newcomers for information on the Jerrems history. He has asked that you be patient, his main dilemma is how to present it. To illustrate how much information is available, currently it takes up about 8 spreadsheets to show everybody, and more will be needed for the “new” families who have just signed up. Ray says that the simplest starting point for understanding how we are related to each other is the migration of some of the main family from Lincolnshire (UK) to Australia in the 1850s. This included 4 boys: |

Letters to the Editor ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

From Sue and Jerry We need to be able to weigh in more thoroughly on this defacing of Jerrems artwork. How do we go about getting a picture of this postcard, perhaps before and after. Of course we could end up in violation of the law or something if the first pic is too revealing I suppose. I will cover my eyes first. Its probably good thing there are no Jerrems in Denmark because they would probably think we were all nuts; its my understanding that no one wears tops on the beaches there (unless they are American tourists). Thanks to Ari for sending the image to us. He also furnished an article that appeared in the Melbourne Age a retrospect arising from the imminent release at a Film Festival of a 50 minute documentary about Carol. Below. |

1) “Vale Street” – one of Carol’s most iconic images. (from Lance)

2) “Mozart St Gang” – a group of Carol’s co-boarders when she was living at Mozart Street, St Kilda (an older suburb of Melbourne, Australia) – I believe supplied by Stephen McNeilly, a friend of Carol’s. (from Lance)

DDENDUM

This Article appeared in the Melbourne Age recently before the film ‘Girl in a Mirror’ featured in the Melbourne International Film Festival.

The ’70s stripped bare

By Peter Wilmoth

July 17, 2005

She was young, talented and ferocious. Carol Jerrems focused her lens on Melbourne’s 1970s sub-cultures in a way that no one else dared to do. Peter Wilmoth reports on a new film celebrating the photographer’s work.

It was when Carol Jerrems was making a film about a gang of 15-year-old sharpie boys from Heidelberg, most of whom had been expelled from school and, in their own words were involved in “bashing, beer, sheilas, gang bangs – which is rape – gang fights, billiards, stealing and hanging out” that she found out most clearly the cost of getting involved with her subjects.

“So far I have myself only narrowly escaped rape but was bashed over the head by the main actor while driving my car, which had just been dented by the rival gang with sticks. They steal my money and cigarettes when I’m not looking, but I refuse to be deterred.”

Very little deterred Jerrems, even the game in which the sharpie boys drew straws to see who would “go off” with her. Her shy, earnest demeanor and angelic face framed by golden frizz belied a ferocious appetite for photographs that would capture the moment, a thirst for the next great shot that could – and sometimes did – endanger her life.

Friend Michael Edols recalls in a new film about her life that he and Jerrems went into a pub in Sydney’s Redfern. “I remember watching Carol in the middle of this room and she turned her camera on this young man and photographed him.” The man grabbed at Jerrems and tore off her necklace while Edols dragged her out of the pub and into the car. “On the way out,” Edols says, “I got whacked in the chest and cracked two ribs. We had every window of the car totally smashed in, including the headlights.”

“Carol was very shy and she didn’t like being shy and she was always pushing against her inhibitions and her limits, and that often led her to dangerous situations,” says Kathy Drayton, the director of Girl In A Mirror, about this extraordinary photographer’s intense, short life. “There was a certain amount of naivety.

“Her photographs engage the viewer in an intimate relationship with her subjects. It’s not always a friendly intimacy – sometimes her subjects look defensive, irritated or even menacing, but you always sense that you’re seeing beyond the mask into the soul.”

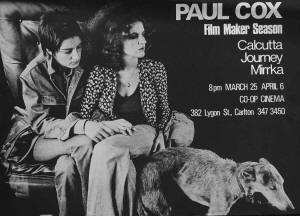

Jerrems was born in Melbourne in 1949, grew up in middle-class Ivanhoe and studied photography at Prahran College between 1967-70, where she was filmmaker and photography teacher Paul Cox’s best student. “She stood out, she was odd,” Cox says in the film. “She had this odd little smile.”

Jerrems had found her calling early. In her second year at college, her confidence was such that she made up a stamp, “Carol Jerrems, Photographic Artist” which she would stamp on all her finished prints. “We were a bit scared of Carol,” former Daddy Cool guitarist Ross Hannaford, who was also at Prahran, says in the film. “She was real serious. Carol was the first feminist I ever met. I remember she gave me a lift home once. I said ‘Thanks, baby’. She said ‘Come here. You don’t call me baby.’ Got a bit of a lecture.”

Jerrems’ success came quickly. In 1972, Rennie Ellis, the Melbourne photographer who died in 2003, opened Australia’s first dedicated photographic gallery, Brummels, in South Yarra and selected the 23-year-old Jerrems’ work as part of its first exhibition, a show called Erotica.

Always carrying a camera and flirting with the idea of danger, Jerrems wanted to capture the raw edges of the world she saw around her, subjects others weren’t focusing on artistically: sharpie subculture, street life and urban indigenous people. “People were stereotyping indigenous people,” said a friend, Ron Johnson. “I think Carol was showing ‘This is not what it’s all about, look, look at the expressions on people’s faces – see what they’re really feeling.”

“People at the time were interested in traditional Aboriginal people while Carol was solely interested in urban Aboriginal people,” says Kathy Drayton. “And at the time, sharpies were considered to be real bogans so it was unusual for someone of Carol’s background to be interested in them.”

Jerrems found work teaching photography at Heidelberg College, in the middle of a tough housing commission area. She was fascinated by the anti-social wildness of the boys, and spent time photographing them swimming in rivers, hanging around in backyards, wearing their skinned-rabbit jumpers, tight jeans and short curtains of fluffy dyed hair.

In this milieu, Jerrems found what Drayton calls the “brash sexuality of Australian youth in the ’70s, a sexuality laced with vulnerability and darkness”, and it inspired her most famous photograph. Vale Street 1975 is a mesmerising portrait of Melbourne model Catriona Brown flanked by two sharpie teenagers, the boys standing just behind in the shadows. The shot was taken at a house in Vale Street, St Kilda, at the end of a long day of shooting. Brown had asked Jerrems to take a shot for her folio, and Jerrems agreed, as long as she could shoot the boys with her, and use the shot for her folio.

The photograph is, says Drayton, regarded as a significant moment in Australian photography “as it bridges documentary realism and the more subjective style of photography that marks the post-modern era”. The power of the photograph was the human connection. “Jerrems does not presume that she is outside the event without influence on it,” wrote Helen Ennis, former curator of photography at the National Gallery of Australia.

Jerrems’ development as a portrait photographer coincided with rising interest in photography as an art form in Australia. Photographers were beginning to be deeply involved with their subjects rather than discreet observers shooting at a distance. Jerrems saw the traditional documentary style of photography as exploitative and believed the more personal collaborations between photographer and subject to be more honest, even if they were more risky personally.

Paul Cox once wrote: “She had to experience everything and feel things deeply before she could record them. She lived to the fullest, then withdrew into her own world.”

Part of the power of Jerrems’ work stems from its reflection of a certain pocket of life in the mid to late 1970s, the world of filmmakers, photographers and other creative types living in group houses. The sexual freedom and youthful confidence of the time, as enunciated and encapsulated by Skyhooks’ Living In The Seventies album, is everywhere in her work. Drayton says Jerrems was “adventurous and forthright in her sexuality”, having affairs with many of her friends, men and women, reflected in her work, “at times seductive, at others, frankly post-coital”.

In the film, one of her great loves, the filmmaker Esben Storm, remembers Jerrems arriving in Sydney with new photographs. “Inevitably they’d be photographs of her waking up . . . with someone. While I’d been off sort of having wild times, she’d be having her wild times. She would sleep with someone and that would mean there would be an intimacy that would allow her to take photographs.

“It was the time of free love in a way, even though we weren’t that free. There were ideals that it was uncool to be jealous and that you weren’t possessive. We all tried to live by that, even though we couldn’t really.”

Greg Macainsh, Skyhooks’ songwriter, remembers Jerrems photographing the band for a book called Million Dollar Riff. “She came to a number of gigs,” he says now. “She was very quiet, reserved. She would make herself virtually invisible. I remember her in the dressing room being very still in the corner. She didn’t take a lot of shots, she would wait for the right moment. She wasn’t a motor-drive type, she was a bit like a sniper, waiting for the perfect opportunity.”

Ross Hannaford was close to Jerrems for a while at Prahran College and remembers the seriousness with which she pursued her photography. “It was a time when there was incredible optimism in the air,” he says now. “If you had a dream, you could do it. There didn’t seem to be anything holding people back. I’d watch Carol shooting and I didn’t realise what she was up to. ‘What are you taking all that rubbish for?’ But when you look back it seemed to encapsulate the times and the life around you. Her work took on a significance later on.”

But amid the gaiety and youthful charge in Jerrems’ pictures, Helen Ennis says a distinct change in mood is evident in the work. “The early photos between 1972 and 1975 were all about optimism. There’s a huge amount of energy in them. It was all bound up with the excitement about the Whitlam government and this desire for change. But from 1976 I don’t think they were anywhere near as optimistic.”

Darkness

It wasn’t just the Whitlam dream fading that gave Jerrems’ work this darkness, nor the mood captured in the Skyhooks song Whatever Happened To The Revolution? (“We all got stoned and it drifted away”). While there is great exuberance in the decade the film documents, there is also a profound sadness about Jerrems’ life. The odd little smile that Paul Cox talks about is rarely seen in the several self-portraits that feature in the film. Instead, there are many hints of the depression that she struggled with. Her friend Robert Ashton, who lived with Jerrems in a group house, remembers her bedroom door being closed for hours and even days.

In 1979, Jerrems went to Hobart to teach. Shortly after arriving she was diagnosed with polycythemia, a rare blood-related cancer. She underwent months of invasive and painful procedures, but came to a realisation she was dying. Jerrems photographed and wrote about her physical decline. She photographed doctors hovering, the scars on her stomach, and her mother, with whom she had a difficult relationship, visiting. As the camera pauses on a shot of her mother, an actress reads from Jerrems’ journal: “She is one of the few people with the ability to push me over the edge into tears or screaming.”

Carol Jerrems died in Melbourne in February 1980, three weeks before her 31st birthday. Her work was bequeathed by her mother to the National Gallery of Australia. In 1990 a retrospective was staged, but until now Jerrems has remained unknown outside photographic and film circles.

Girl In A Mirror gives an insight into the counterculture of the 1970s – the music, the cars, the fashions, the social tensions, the sexual experimentation. Kathy Drayton, with help from the National Gallery of Australia, had access to hundreds of Jerrems’ photos as well as shots from Rennie Ellis (who photographed Jerrems often), friend Robert Ashton and Henry Talbot. The journals Jerrems kept after 1975 are used to “narrate” the film.

Drayton, who has worked as an editor with SBS television as well as editing a variety of independent experimental films and short dramas, says her interest in Jerrems was piqued when she saw three of her photographs at a New South Wales Art Gallery exhibition. The “deceptively simple power and beauty” of the three photos haunted her, and she began to research Jerrems.

“There’s an emotional intensity and intimacy with Carol’s photographs,” she says.

Who was Carol Jerrems? “There were a huge number of perspectives from people about Carol,” says Drayton. “She went into roles with people, played games. She became whatever people wanted her to become.”

Girl In A Mirror will screen at 3pm on Saturday, July 30, at Greater Union, corner Russell and Bourke Streets, as part of the Melbourne International Film Festival.

The Film has also appeared in other festivals including the Sydney and Wellington Film Festivals.

This is the short description of the film on the Melbourne International Film Festival Website:

Welcome aboard to Jesse Jerrems (not named after the outlaw Jesse James), who signed up recently for the Journal. Jesse is 23 and lives with his parents and older brother Rick (a gourmet chef) at Noosa Heads, a popular seaside resort on the Queensland coast (pictured above). He works for his father Rob in a design and supply company.

Welcome aboard to Jesse Jerrems (not named after the outlaw Jesse James), who signed up recently for the Journal. Jesse is 23 and lives with his parents and older brother Rick (a gourmet chef) at Noosa Heads, a popular seaside resort on the Queensland coast (pictured above). He works for his father Rob in a design and supply company. The Jerrems Journal Recruitment Committee (Ray and Di Jerrems) recently returned to Sydney from a successful recruiting campaign in Auckland, New Zealand, having signed up their baby grand daughter Jessica (“Jess”) Louise McDonnell.

The Jerrems Journal Recruitment Committee (Ray and Di Jerrems) recently returned to Sydney from a successful recruiting campaign in Auckland, New Zealand, having signed up their baby grand daughter Jessica (“Jess”) Louise McDonnell. The following letter is in response to the last edition in which the famous Carol Jerrems photograph was featured by Roving Reporter Ray; the photo was cropped in some publicity material by the local museum in the interest of decorum.

The following letter is in response to the last edition in which the famous Carol Jerrems photograph was featured by Roving Reporter Ray; the photo was cropped in some publicity material by the local museum in the interest of decorum.