Jerrems Family Newsletter

Dear Donald,

together long ago. Improved transcontintal

transportation systems become part of the family lore.

Enjoy Ray’s account below.

Place your mouse cursor over the image to view

the caption text.

Every December we try to offer greeting to each other

through the journal.

This year we plan to send images of old family

Chrismas cards…the ones with family photos at the

time.

Recently, I found one from our 1948 family. I plan to

use it in the December issue. If you have one you

would like to include, digitally scan it and send me a

copy.

| A Tale of Two Railways |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian

Connections by Railway

Introduction

Recently I have been reading about the history of the

construction of railways in the United States, for two

reasons. The first reason is that I have been very

interested in railway history in New South Wales since

I was a small boy (for reasons I will talk about later in

this article), so it seemed logical to compare it with the

railway history of the United States. The second

reason is that it forms a backdrop to the history of

parts of the Jerrems families in New South Wales and

the US.

Melbourne readers have the picturesque “Puffing Billy”

railway line which climbs up the Dandenong Range

from Emerald, but as far as I know this railway does

not have any specific relevance to the Jerrems

families of yesteryear.

Readers like Sue Jerrems, who has a miniature

steam train line in her garden in Los Vegas (plus a

Pullman car and a caboose), will particularly

appreciate this article. But I am sure that everyone

else will enjoy it too.

I dedicate this article to Jerry lV (William George

Jerrems lV), Sue’s late husband and a fellow steam

train enthusiast.

The New South Wales family’s

railway connection.

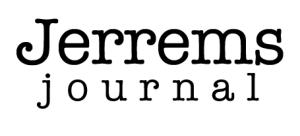

Briefly, my interest as a boy in the history of railways in

New South Wales was piqued by accounts from my

grandparents of their train trips across the Blue

Mountains (to the west of Sydney) in the late 1800s. In

those days the railway was a single track railway

which had the famous “Zig Zag” (pictured

above) at the western end of

the Blue Mountains to enable it to descend the

western escarpment. My grandfather Alf Jerrems

lived

in Sydney, and my grandmother Esther grew

up in

Lithgow, a short distance beyond the Zig Zag. In their

courtship days they travelled a lot along this route by

train to see each other, and after they married in 1905

and settled in Sydney they continued use the railway

on occasions to visit the numerous Lithgow relations.

If the Zig Zag hadn’t been built my grandparents would

never have met and I would not be writing this article

today.

I will tell you more about the remarkable “Zig Zag” after

telling you about the US connection.

The United States family’s railway connection

The United States family’s connection with railway

history is also interesting. When William George

Jerrems (my grandfather’s uncle, and Jerry lV’s great

grandfather) and his young family sailed from

Sydney to San Francisco in about 1876 they would

have travelled to New York by train, along the recently

opened Transcontinental Railroad (using a generic

term for it). A spectacular feature of this railway,

comparable with the Blue Mountains Zig Zag, was the

way it climbed from Sacramento over the Sierra

Nevada Range through the legendary Donner Pass.

Like the Zig Zag, the Donner Pass section of the

Transcontinental Railroad had been described at the

time as one of the world’s major engineering feats. A

big difference between the two railway journeys was

that it took five hours to travel from Sydney to Lithgow

and at least five days to travel from San Francisco to

New York.

In later years William and his father-in-law

Alexander Nicoll opened “Nicoll the Tailor”

stores in San Francisco and Sacramento, so they

would also have travelled along this railroad on a

number of occasions.

If there had not been a railroad from San Francisco to

New York when the family landed in San Francisco

then perhaps our editor Donald’s great grandparents

may have settled in San Francisco and (like me)

Donald would not be editing this Journal.

The Zig Zag Railway

Now known colloquially as the Zig Zag Railway, the

first railway over the Blue Mountains was commenced

in 1866 and completed in 1869. Its significance was

that it opened up railway access to the vast area of

western New South Wales, replacing rough roads

used by slow horse carts, horse coaches and bullock

wagons.

To understand the meaning of the term “zig zag” you

need to imagine a road descending a steep mountain

using a series of “hairpin bends”, but replace the

bends with overruns where the trains stopped and

then reversed down the next section, then forward

down the next section. Then put in long stone arched

bridges to cross the gullies in between.

In some parts of the “Zig Zag” section workmen had to

be lowered down the cliffs to drill holes for blasting,

and in one instance 2 tons blasting powder was used

to remove 45,000 tons of rock in one huge explosion.

A party of dignitaries travelled up from Sydney for the

occasion, and the explosion was set off by the State

Governor’s wife.

In fact the railway descended a total of about 1000 feet

into the valley (not a lot compared with the United

States Trans Continental Railway) from the top of the

range at Clarence Tunnel. For the most part its fame

was probably due to the novelty and ingenuity of its

construction and its huge impact on the opening up of

western New South Wales, rather than the immensity

of the work carried out.

The Zig Zag part of the railway became rather

notorious for trains running away on the steep

gradients, mainly involving goods trains. When there

was a pile-up the townspeople of Lithgow (including

my grandmother) flocked along to look at the results.

On one famous occasion a steam engine crashed

through the buffers and almost toppled over a high

cliff. Luckily its progress was arrested by rocks before

it overbalanced.

This section was replaced by tunnels in 1910, ending

an era.

The United States Trans Continental Railway

I have used the term “Trans Continental Railway” for

ease of reference (it was called the Central Pacific

and the western part was owned by the Union Pacific

Company, which gets complicated). Its significance

was that it opened up railway access between the

eastern and western coasts of the United States,

replacing (a) a long and dangerous trip by wagon train

across the United States (b) a laborious sea voyage

from the East Coast around the bottom of South

America and up the West Coast to San Francisco or

(c) a boat trip on the East Coast down to the Panama

area, a land trip across to the other side, and a further

boat trip to San Francisco (these were the routes used

in 1849 by the “Forty Niner” gold miners to get to the

gold fields near San Francisco).

Although the founder of the railroad, Theodore Judah,

first conceived a practical plan for the building of such

a railway in 1860 it took him several years of

intermittent exploration to work out how it could

actually ascend the San Francisco side of the Sierra

Nevada Mountains, near San Francisco. He finally

chose a route across Donner Pass, previously used

by settlers’ wagons. This part took a small army of

workers five years to construct, and involved very steep

gradients up a winding route, and the construction of a

complex system of cuttings, bridges and tunnels.

In

1869 the railway was opened along its full length with

great fanfare.

In one section the ascent route to Donner Pass

wended its way along the rim of the American River

Canyon, in some cases 2000 feet above the river.

Starting near Sacramento almost at sea level the

railway climbed to a little over 7000 feet (2134

metres), a huge climb for the small steam engines

used in those days. For the benefit of Australian

readers the Pass was almost as high as our highest

mountain, Mount Kosciuszko.

The winters were severe on the heights of the range,

raising unexpected problems of winter snowfalls.

Eventually a total of 30 miles of “snow sheds” were

built over the high sections to keep the snow off, and

snow plough teams were kept on standby.

Although the Donner Pass was one of the highest

railway routes used in the United States, it was by no

means the highest. This honour goes to the Alpine

Tunnel on the narrow gauge South Park Line in

Colorado, at nearly 12000 feet (3658 metres). Opened

in 1882, it was closed in 1910 because it was

impossible to keep open due to high snowfalls.

The Donner Pass section of this railway was

superseded in the 1990s by a tunnel.

The engines used on the US Transcontinental

Railway and the Zig Zag

The engines used by our relatives in 1876 (in the US)

and in the very early 1900s (the Zig Zag) were quite

different, primarily because the engineering had

improved significantly in the intervening period.

In the United States a particular design was used

from the 1850s well into the 1880s, involving a wheel

configuration of 4-4-0 (4 small wheels at the front, 4

connected big wheels in the middle, and none under

the cab), known in the USA as the “American”. Similar

designs were used in New South Wales at the time

also. It is this type of locomotive that would have

hauled the Jerrems family’s train in 1876, with the

assistance of an additional engine up the steep

grades to Donner Pass.

The brightly coloured trains of this era, with their large

timber cabs, polished funnels and large head lamps

and cowcatchers, probably reflected the romance of

the period.

By the mid 1890s in New South Wales the more

sedate-looking P6 (later renumbered as the “32

Class”) was hauling trains over the Blue Mountains.

This was a more powerful loco with a 4-6-0

configuration, having 6 smaller connected wheels in

the middle. These engines would have hauled the

trains used by my grandparents, assisted on

occasions by another engine “double heading” on the

front.

Memories

Hopefully you have some restored steam trains which

operate occasionally in your area, or there are

miniature steam trains there, to remind you of the

marvellous days when steam trains reigned supreme.

Or perhaps you have a small grand daughter named

Jessica (as I have) who has a toy steam engine which

has a whistle which sounds just like a steam train

whistle. It takes me back to the whistles I used to hear

echoing in the Blue Mountains when I was a boy, and

to my grandparents who would have done likewise.

No doubt you have memories also.

The caboose/guard’s van has arrived

When you are watching a steam-hauled goods train

passing by, you know when the end of the train is

getting close because you see the caboose

approaching (in the United States) or the guard’s van

approaching (in Australia). The caboose/guard’s van

has arrived for my article and it is time for me to sign

off.

It has been interesting to see how two of the best

known railways in the world had a connection with the

Jerrems family, and that without these railways

perhaps many of us would not be here today.

| Image Old Engine |

| Image Old Tunnel |