Dear Donald,

|

| A wedding announcement |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian

ELOPEMENT

On Tuesday night, Mr T. Jerrems, the eldest son of the burgess constable of Gainsborough, having a chaise in readiness outside the town, eloped with the daughter of Geo. Jepson, Esq. a young lady of great personal charms. They galloped through Brigg, crossed the Humber at New Holland ferry, having first locked up all the oars and sculls to baffle pursuit, and at nine o’clock in the morning they were married at Sculcoates. A brother and uncle of the lady traced her, but arrived too late to prevent the nuptial knot from being tied.

This report was published in the Chelmsford Chronicle

on Friday 9th June 1837.

But who was T. Jerrems, who did he elope with, and why did they elope?

Read on dear reader, and all will be revealed!

The people involved in this high drama were none other than my great great grandfather Thomas Cane Jerrems (b1815), and the “young lady of great personal charms” was my great great grandmother Elizabeth (nee Jepson) b 1816. The “burgess constable” was Big Bill, and Elizabeth’s father was the surgeon George Jepson.

The account of the elopement conjures up pictures of the couple reaching their clandestine rendezvous outside the town in disguise, followed by the small coach rushing dramatically off into the darkness, to the accompaniment of the thundering of hooves, the cracking of whips and the coachman bellowing to the horses to gallop faster. Added to this was the nail biting question of whether the couple would be caught by the posse close behind.

Sculcoates, apparently the local equivalent of the famous Gretna Green, is now a suburb of Hull, 66 km north of Gainsborough. This would have been quite a distance to travel on the rough roads of the time, particularly at night. Changes of horses would have been needed, showing that Thomas had given some thought to the adventure.

Although the name of the church is not stated in the article, it is very likely that it was St Mary’s Church (see drawing below)

Although the elopement appears to have genuinely been a cloak and dagger affair, perhaps a certain amount of imagination had been applied by the newspaper reporter (for instance why would it have been necessary for the chaise to have been kept in readiness outside the town?). On the other hand it all makes a ripping yarn. Why let facts get in the way of a good story, I always say. Good on you Tom and Liz!

| Why elope? |

The normal connotation of elopement is that one or both parents have refused to consent. For those days Thomas (aged 22) and Elizabeth (aged 21) were at an age when couples were frequently married, so it is difficult to see why consent would have been withheld merely on the grounds of the couples’ tender age. Thomas could scarcely be accused of cradle-snatching.

Another reason for elopement has been because the lady’s father fears that the dastardly swain has designs on the lady’s dowry or inheritance. With upwards of a dozen siblings one would doubt the size of Elizabeth’s inheritance.

The most likely explanation is that Elizabeth’s father (George) did not approve of the match due to his family’s eminent background. This background was described in my article of July 2009, where I said that his father (also named George) was the Prebendiary at Lincoln Cathedral, and his grandfather William was chief legal adviser to the diocese’s Ecclesiastical Court. Elizabeth’s brother Octavius (a doctor) was privately educated, so it is probably that Elizabeth and her other siblings were privately educated also. On the other hand Thomas and Big Bill were shopkeepers.

The sequel to the romantic notion of elopement must have been anti climactic. The couple were not banished to the Antipodes to forever atone for their sins. Instead, after the euphoria had evaporated they would have returned to Gainsborough and settled down to the mundane (but important) tasks of having children and selling groceries. Had all been forgiven?

| Children |

Thomas and Elizabeth had the following impressive brood of children (all born in Gainsborough):

- Thomas Clarke Jnr b1838 d 1902, South Australia

- Frances Jane b1841, came to Australia with family in 1859 but returned soon to England. Nothing further known.

- William George b1843 d1905, ancestor of many US readers.

- George Jepson b1844. Came to Australia, sighted occasionally.

- Edwin Lewis b1845 d1873 South Australia.

- Charles b1847 d1927 Sydney. Charles was source of the NSW families.

- Robert Cane b1849 d1888 Richmond Victoria. Source of number of Victorian families.

- Catherine b1850, d1930 Armadale Victoria. Never married.

- Arthur Reginald b1852, d1934 Brighton Victoria. Source of number of Victorian and Queensland families.

Selling groceries

The 1851 Census shows Thomas, Elizabeth and eight children (Arthur had not been born) and three servants living in Mandarin House, Silver Street, Gainsborough. Thomas describes himself as a grocer, and I have previously presumed that the family lived over the shop.

| The Ancient Order of Shepherdesses |

An 1845 newspaper article refers to the annual general meeting of the quaintly named Ancient Order of Shepherdesses, of which Thomas was the secretary, where a large number of the sisterhood sat down to tea. The choir of the Holy Trinity Church donated their services and sang several pieces of music.

The name “Ancient Order of Shepherdesses” conjures up images of nubile shepherdesses tending their sheep in arcadian fields. But how did this apply to the ladies of the town of Gainsborough?

With slight variations of name (eg “The Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherdesses”) these societies were classified as “Friendly Societies” which, as some readers may recollect, more commonly took the form of a society which provided support for death or sickness in illness or death in a family in return for regular subscriptions. However some friendly societies provided social activities, often on a quasi -masonic basis, such as the shepherdess societies for women and the Ancient Order of Foresters for men.

One of the speakers at the annual general meeting was a Mr Burbank, “who on this occasion was a friend in need”, and the Vicar and the Reverend C. Hensley had been intending to attend to give addresses but were unable to do so. These aspects, plus the attendance of the choir, give the impression that the society’s activities extended beyond socialising for women to helping the community.

Presumably Thomas was the secretary because his wife Elizabeth was also a member. It is interesting that they took this interest in community affairs.

The term “shepherdess” could originate from “good shepherdess”, which in turn is derived from a description in the Songs of Solomon in the Bible.

I have seen references to some of Thomas’s brothers being Masons (Robert was a member of the Ancient Order of Oddfellows), so it is likely that Thomas was a Mason also. Perhaps his experience with the Masons was the reason why he had been asked to be secretary

Thomas and the Gainsborough Poor House Union

Relax, Thomas and Elizabeth were not incarcerated in a poor house! Thomas, with two other Gainsborough grocers, had merely entered into a contract with the local Poor Law Union in 1845 to provide groceries to the Gainsborough Poor House and other poor houses in the area.

Poor houses catered for unemployed men and women, widows and their children, the aged and infirm, low-risk lunatics and the intellectually disabled. They were quite well funded, and the contracts would have been lucrative. The grocers would also have required to hold a lot of stock and to make regular deliveries.

The background to these unions was that the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act provided for the appointment of “Poor-Law Commissioners” and the setting up of administrative areas called Unions. Rates were raised in these areas to fund the building and running of poor houses.

| Thomas digs for gold in Australia |

Thomas travelled to Australia , arriving in Melbourne on 23rd November 1851 on the 916 ton sailing ship “John Fielden” and in 1852 took out a mining licence in the Mount Alexander area, about 125km (at least four days walk) north of Melbourne. A letter to Thomas returned unclaimed from Mount Alexander tends to confirm that he stayed there for a while but then moved on.

The discovery of gold there was first reported in the Press in September 1851 and within a year the goldfield boasted a digger population of over 30,000, and was known to millions around the globe. It had become the richest shallow alluvial goldfield in the world.

A curious aspect is that this was the first major gold strike in Australia, and Thomas would have left England some months before news of the strike had reached there (taking into account the fact that the mail ships would have taken almost four months to carry the news to England).. So Thomas would not have left England with the intention of mining gold, nor would Melbourne have shown any signs of the prosperity which later resulted from the gold strikes. At the time Thomas left England Melbourne was little more than a large town with a population of 25,000, only about three times the population of Gainsborough, and with a similar reliance on local rural industries.

No doubt Thomas would have encountered Melbourne’s heat as soon as he arrived, and would have noticed it even more travelling to Mount Alexander during summer. A big contrast with the Gainsborough climate.

Although Thomas would have been fairly used to lifting heavy sugar and flour bags and other groceries, gold fossicking would have been far more arduous. The high temperatures and hard work would have come as a shock to him, particularly as he would not have been intending to go gold digging when he set off from England.

A succession of discoveries in Beechworth, Ballarat and Bendigo meant that the Mount Alexander miners could move on to those areas without loss of continuity. Thomas possibly did this, but would have had to set off for England no later than mid 1853 at the latest (see later).

Statistically speaking only one miner in four was able to find useful amounts of gold, so Thomas’s chances of finding fame and fortune would have been slim.

Migrating to Australia at a time when seven children were under 10 years old and Elizabeth was expecting Arthur (although perhaps Thomas did not know at the time that she was “expecting”) was a big step, and was a far cry from the romance of their original elopement.

| Did Thomas return to England? |

Amazingly, I have concluded that Thomas returned to England and then came back to Australia, a proposition I had previously discounted because it sounded so unlikely. Miners quite often returned to their country of birth, but for a person to do this and then return to the mining country must have been almost unique in those times when each voyage took about four months! Also, the trip back to England was equally as rough and protracted as the trip to Australia because the route crossed the Pacific Ocean and passed through the Magellan Straits near the southern extremity of South America.

The lady from Gainsborough who carried out the Jerrems family research in the UK located a Passenger List for the sailing ship “Salem” which left Liverpool, bound for Melbourne, on 6th December 1853. This showed Thomas and Thomas Jnr to be passengers. It would have arrived in Melbourne in about March 1854.

She had not located the earlier records, so she assumed that the 1853 trip was Thomas’s first trip.

It seems therefore, from the records located by me, that Thomas returned to England after his gold fossicking venture. He would have had to leave Melbourne no later than mid 1853 in order to set off again to Australia in the Salem in December of that year.. Perhaps he returned to England intending to bring the family out to Australia, or possibly when he returned to Gainsborough he changed his mind about settling back into humdrum Gainsborough life. Possibly Elizabeth was unwilling at that stage to undertake the comparatively dangerous trip to Australia with such a young family (for instance Arthur was still a toddler and six of the other children were under 10 years of age), with the rough seas of the Roaring Forties and where fatal sickness on board the ships was common. Whatever the reason, Thomas returned to Australia with only his eldest son Thomas, aged fifteen.

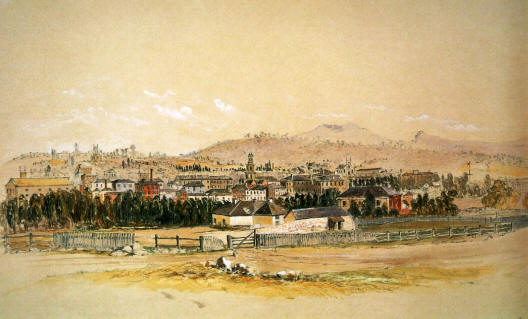

| Thomas goes to Hobart Town |

of Thomas the international traveller was in April 1854 (soon after the date

he and Thomas Jnr would have arrived in Melbourne from England) when he

sailed to Hobart Town (pictured and in the header) in the ship “Tasmania”.

He must have decided that the prospects were better in Melbourne because he returned to Melbourne from Tasmania and presumably rejoined his son.

Thomas’s business ventures

After his earlier dabbling as a gold miner Thomas Snr tried different ventures, including businesses as a merchant, an estate agent and a money lender.

He is recorded in the 1856 Electoral Roll Directory as being a merchant in Melbourne’s Little Bourke Street, which coincidentally was close to the shop of Nicoll the Tailor (readers may recall that Thomas’s son William later married Nicoll’s daughter Mary).

A spate of advertisements in the Melbourne Argus between early June and late October 1859 heralded Thomas’s arrival in the real estate arena, showing that he had set up a real estate business in the Mechanics Institution Building in central Melbourne. At the same time he advertised that he had up to 3,000 pounds available for loan, possibly intending that loans would be used to finance purchases of properties. At a time when the asking price of residential properties was in the vicinity of 200 pounds each it is obvious that 3,000 pounds was an enormous amount of money.

Properties offered for sale were mostly cottages and land in the Richmond area. Exceptions included three rural farms (two of which were 15 acre and 50 acres), and blocks of land at the seaside village of Brighton for the princely price of 15 pounds each. A six room house at Richmond and a property in Spencer Street Melbourne were also offered for letting.

The advertisements ceased at the end of October 1859, indicating that he had abandoned the venture.

| Elizabeth finally arrives in Melbourne |

Finally, after mature deliberation over a period of almost 8 years Thomas was reunited with Elizabeth and most of the family in Melbourne in January 1860. Elizabeth, Frances, Robert, Catharine and Arthur sailed on the “Lincolnshire” from London in September 1859 and arrived in Melbourne on 21st December (what a wonderful Christmas present?). This does not account for William, George, Edwin ad Charles (all located by me in Australia), who may have come out separately.

The family settled down in a modest house in the modest suburb of Richmond, in inner Melbourne, and perhaps Elizabeth felt that normality had returned to the family. But several years later Thomas, in a fit of absent mindedness, fled the domestic scene again, leading Elizabeth to advertise in Australian and British newspapers asking him to return. He did this, only to die a few years later.

His death notice, published in the Argus of 27/11/1866 was cryptic in the extreme:

Jerrems. On the 14th inst, at his residence, Richmond Terrace, Richmond, MR T.C. Jerrems, late of G., Lancashire, aged fifty-one.

| Next article |

As often happens, my intentions of writing a single article have been thwarted by the amount of information I have accumulated, a situation which I blame partly on Alan Fitz-Patrick, who sent me the elopement, Shepherdess and Poor Union articles.

In a later article I will follow the story of Thomas’s widow Elizabeth and some of her lesser known children.