Dear Donald,

Our journeys of the past six months have been varied:

- November to Willingham UK (olde Jerrems hometown)

- January to South Australia State Library

- February a surprise visit to to our Scottish Connection

- This month to Hartley Vale New South Wales , Australia

Not sure where we will visit next month. The US Census Bureau released the 1940 results to the public this month. It is a boon for ancestry researchers, so stay tuned.

| THIRD SASSALLS ARTICLE |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian

Revisiting Ray’s Grandparents Hometown

Introduction

Since writing the articles about my Sassall great grandparents (see Journals of March and April 2011) my wife and I spent several days exploring the Lithgow area to get the feel of my great grandparents’ environment. The previous articles had been prepared from notes given to me, with my distant recollections; I had not been back to Lithgow for over 40 years.

Most of the industrial areas which had been hives of activity have now gone. For someone like me who had seen the hustle and bustle of the steelworks and the railway shunting yards the silence is almost eerie.

The house and blast furnace

The house occupied by my great grandparents near the steelworks has gone, replaced by a commercial building. Fortunately all of the other little nearby cottages are still there, tucked together in neat little rows, their condition belying the fact that they are all well over 100 years old. Built from local timber which was in large supply at the time, they are on narrow blocks.

Starting about 50 metres behind the cottages, on a low rise, are the remains of the steelworks. This would have made a very convenient short walk to the steelworks for workmen, but the noise around the clock would have been tremendous. In addition to the periodic crashing of the giant furnace doors there would have been the thumping of the huge steam engines which forced air unto the furnaces, noises which I remembered from my visits to steelworks as a schoolboy.

The baker’s run

The next significant element of our research was to follow the route my great grandfather took in the 1800s when he was delivering bread to nearby villages, and where he originally met my great grandmother. As mentioned previously, this route went over Brown’s Gap to a somewhat confusing collection of localities containing the name “Hartley”, consisting of Hartley Vale, Little Hartley, and past Middle Hartley Road to Hartley.

The road up to Brown’s Gap was not as long or as steep as I expected, making it very surprising to find a panoramic view of picturesque Hartley Valley from just beyond the Gap, showing the farms on the floor of the valley and the surrounding sandstone cliffs. After a long and very steep descent into the valley we drove past Collitts Inn, a landmark dating back to the construction of the first road across the Blue Mountains and arrived at the village of Hartley Vale.

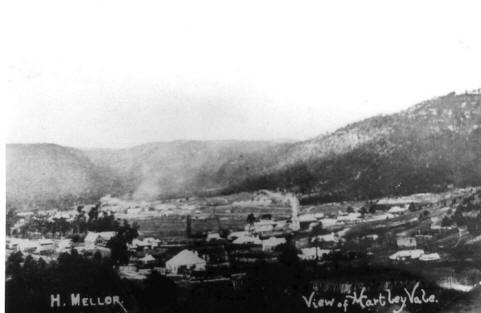

Hartley Vale

The village is now a ghost town, belying the fact that in the 1880s there were 12 pubs, a school, stores, and numerous houses built by the Hartley Kerosine Oil and Paraffine Company on the 30 acre site the company had bought.

All that remains of the buildings are the Comet Inn (pictured below), built in about 1879, and a handful of very old cottages. Initially I guessed that the Inn might have been named after Halley’s Comet, but in fact it was named after the Comet brand of kerosene produced at the time.

When my great grandfather first drove his bread cart into the village he would not have imagined that his wife-to-be (Susannah Druery) was a schoolgirl in the village, possibly in school at the time. Nor would he have imagined that in one of the small valleys nearby her father and brothers were shale miners in a little-known operation that forms a significant part of the history of New South Wales.

I will describe the shale mining operation first, and in a later article I will take you on a historic trip following the footsteps of my great grandmother Susannah.

Shale oil refining

The production of shale oil and its by-products represented a major advance in technology which was to have a significant effect on many countries in the mid to late 1800s. Prior to its discovery households relied on tallow lamps burning animal fat or whale oil for lighting. Heating was provided by wood or coal fires. The discovery of shale oil changed this completely.

The potential of oil shale (now known as torbanite) was recognised by an immigrant in Canada named Abe Gesner just prior to 1850. He discovered that shale oil could be obtained by heating torbanite (a fine-grained sedimentary rock), and valuable by-products could also be obtained. High temperatures were required for the heating, and the resultant gas had to be distilled, requiring quite complex processes (see later). Also, coal fired furnaces were required to produce the necessary heat. For these reasons it took quite a while for the technology to be developed and adopted, and further developed over a number of decades.

Shale oil itself was similar to modern oil, which could obviously be burnt for industrial purposes, but for the proverbial “man in the street” the huge impact was provided by the by-products of kerosene and paraffin. Kerosine provided a low volatility source of lighting and (in the 20th Century) heating. Unlike petrol or methylated spirits it did not did not readily catch on fire and could therefore be quite safely used in homes. Paraffin was used to make candles, which were used in every household.

Australia seems to have been comparatively slow in embracing the new technology. In New South Wales Port Kembla, Hartley Vale and Joadja (near Mittagong) were probably the first areas, in the 1860s, followed over 30 years later by works at Newnes (north of Hartley Vale).

Stumbling blocks for shale oil production

One of the stumbling blocks to adoption of the technology in Australia was the amount of coal required for heating the oil shale. In Hartley Valley (and later at Newnes) the oil shale seams and coal seams were near each other, removing the problem. Another stumbling block was obtaining the means of importing the necessary machinery into the sites, and exporting the products to market.

Amazingly when the shale was first mined in Hartley Vale in 1865 it was laboriously hauled by bullock wagon over the Blue Mountains to Penrith, where it was carried by rail to Sydney for processing. Some was shipped to Melbourne. As the railway was built westward from Penrith the bullock wagon trips shortened, until the railway reached Hartley Vale Station at the top of the scarp in 1869. The station was reached initially by a ropeway and later by an inclined trolleyway, finally enabling the products to be sent by rail to Sydney.

Another problem was the inefficiency of the processing methods and the need for improvement of the technology. Initial setting up of the processing plants and introduction of improvements was very expensive. For instance, in addition to the machinery, a huge number of bricks had to be made for the kilns and a permanent water supply was needed.

Production of the shale oil

In simple terms the shale was “cooked” in furnaces called “retorts” and gases were produced. The draw off of the gases occurred at different points up the retort, depending on the ‘fraction’ or specific gravity of the gas at that point to thus yield different products (e.g. naptha, heavy oils etc). Initially the retorts were horizontal but later they were vertical, allowing far greater heat to be generated.

Mining the shale and coal

Here is where miners like the Druery family made their contribution to this industry. The mining of coal was well established, and the techniques were equally applicable to the mining of oil shale. They both occurred in horizontal seams in the Hartley Valley which were accessible from the floor of the valley.

The book “A Light in the Vale” owned by our reader Graham Harmer tell us that:

“Shale miners were generally paid more than coalminers. They worked the shale seams with picks, bars, hammers and wedges, chasing the deposits of shale until they reached ridiculously small thicknesses. Oil shale had a tendency to fracture with razor-fragments flying out from the face. Quite a few miners suffered very severe cuts from flying shale…Many a man lost an eye or severed part of a limb. You would find them with great scars on their faces…”.

The inhaling of dust by miners was also a major concern, three of my mother-in-law’s four uncles died from “dusting” as the result of gold mining in the Ballarat (Victoria) area before the First World War.

Mining is still a hazardous occupation, but in those days it was downright dangerous. There was no State supervision of “Occupational Health and Safety” and mine collapses were quite common. The work was also very demanding. The hours were long and conditions tough. Often the miners had to swing their picks from a crouching, kneeling or reclining position and haul the coal or shale out on trolleys on all fours. In gold mines small tunnels known as “rat holes” were initially dug by miners to try to follow a seam.

Looking at the list of interments in the Hartley Vale Cemetery, I was struck by the number of deaths of men in their 20s and 30s. I wonder how many deaths were due to mining accidents? The Lithgow “Mercury” has many references to accidents in mining – including a major one at Hartley Vale at the turn of the century. There is also perhaps an irony that the name Hartley came from a mine in England where 264 miners died in a fire.

Popularity of kerosene and candles

No doubt the comparative safety of using kerosene for lighting (and later for heating) was a big factor in its adoption. Candles were also an essential item for lighting, the difference being that candles were much easier to light and extinguish than kerosene lamps. My mother-in-law, who turns 100 this year, says that her father left a kerosene lantern burning in the kitchen all night. Each of the numerous children had a candle which they could light in their bedroom and blow it out when required.

In the cities gas and electric lighting was introduced in the 1880s and 1890s, but in the country (representing over half of the households at that time, possibly half a million) kerosene lamps and candles were used for many decades. The size of the market was huge.

The production costs for shale oil were high, and the equipment was very expensive to construct, leading to the adoption of use of mineral oil for most purposes (including the production of kerosene) from overseas after the First World War. It was significant that the Joadja works and the Hartley Vale works ceased production in the early 1900s. Production of shale oil made a brief appearance during the Second World War at Glen Davis, but then vanished.

Life in Hartley Vale

A modern day visitor to the area would be struck by the pretty setting of the village, with its backdrop of mountains, but in the days when the Druerys lived there in the late 1870s the minds of its inhabitants would have been concentrated on much more mundane and compelling matters. Housing would have been very basic, the pay would have been poor and the winters would have been chilly.

How long did the Druerys live at Hartley Vale?

Susannah’s mother and at least one sister did not come to Australia, settling instead in the Seattle area in Washington State, USA.

Although my research is incomplete, it is probable that Susannah, her father Robert, her brothers Thomas Glanville and George Henry and her sisters Annie and possibly Mary Hannah (who later moved to Seattle) stayed in Hartley Vale for about two years (1878 and 1879) after migrating from England. They then briefly moved on to the Wollongong area on the coast and the Nowra area. Her father and two brothers returned to the nearby Lithgow area, where her father died in 1903. All the men worked in later years as coal miners

Next article

In the next article we will continue our journey from the Hartley Valley along Fred’s bread carting route to the historic “Rosedale” inn, where Fred met Susannah.

| Administrivia |

Donald Jerrems

Keeping the Mailing List Current

Our Jerrems Journal mailing list is manageable and we try to keep it up to date. Here is a breakdown:

- We send to 44 active and two inactive, bounces, or non-existent address.

- 23 are located in the US; 19 in Australia and 4 in Europe.

- 20 are surnamed Jerrems (many are husband & wife or brothers and sisters).

- The two bounces are: jhawk84@sprintmail.com Charles Keller llgray@virtualcity.com.au Laurel and Laurie Gray

We count on family connections.

If you have a new email addresses or know of a Jerrems not on the list, drop Ray or myself a note.

And we love old Jerrems family photos…send us one found in your attic, so we can tell the story.