Dear Donald,

| Introduction |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, and Historian

In my first article about Percy I left him in the beautiful rural area of Kirklands in Tasmania on the eve of the First World War. Readers will remember the story about his head-on collision, his training as a Presbyterian minister, and his early married days with his wife Florence and young children Alec and Margaret. The article finished on the eve of the First World War, during which Percy signed up for service in France.

| Percy’s signs up for service |

At the age of 36 Percy took the dramatic step of volunteering for the Army as a Chaplain. Having obtained a commission as Captain he embarked from Hobart in July 1916 to serve in France. After spending some time training in England, he was finally despatched to France in early 1917.

Percy served with the 40th Battalion (part of the 10th Brigade) from April 1917 to January 1918.

Previously the battalion had embarked for the Western Front in July 1916 and by December was serving in the trenches in France.

| The big picture of the war in France |

I had written articles about ancestors who had served in the First World War without having any idea of the “big picture”. All the battles resulted in horrific casualties on both sides, giving the impression that the battles were of immense strategic importance and could have affected the outcome of the War. However this was rarely the case unless the battles were part of a major offensive. In other cases they were of comparatively minor military importance and may have been mounted to capture an area of high ground or to merely straighten the alignment of a defence system.

Basically for almost the whole of the War there was a single trench system snaking its way through the whole of Belgium and France from north to south, the location of which was determined by the extent of the early German invasion in 1914 which had been arrested by the French and the British Expeditionary Force. For the next three years the line moved backwards and forwards for a small number of miles, as the result of numerous skirmishes and battles.

In broad terms the German objective was to cross Belgium and the north of France to capture the northern Channel Ports and use these to invade England. The Allies were of course intent on stopping this. Most of the land was flat and (particularly in the notorious Somme area) poorly drained and prone to flooding from rainfall.

Another German objective was to capture Paris. The objective of the French armies and later the American troops was to prevent this.

| The German defensive systems |

We read about the Hindenburg Line as being the definitive military defensive line, but the German defensive line along the trench system was also large in strategic places. These lines were sophisticated and were built up from 1914 using materials brought in by railway. Particularly on high ground which commanded the future areas occupied to the west by the Allies, they built numerous concrete “pillboxes” and (where the soils allowed it) deep tunnel systems. Often the “high ground” was only a few metres above the surrounding countryside. Barbed wire was also used to protect defences.

The pillboxes were made of thick concrete (over half a metre thick) and were virtually shellproof, often with deep bunkers underneath for the troops who lived there permanently. Some were huge and some were compact. They had apertures for firing machine guns which had an effective range of well over 1,000 metres. They were also used as observation posts for directing artillery fire to disrupt Allied army build-ups, to repel Allied attacks and to locate Allied artillery positions. They were a continual thorn in the side of the Allies.

| Tunnels |

Regarding the tunnels, both sides had “dug in” to their respective positions, digging down to obtain protection from the incessant shelling. This produced, particularly for the Germans, a maze of tunnels sometimes going down 12 metres which were used for storage bunkers and sleeping quarters. However the Allies had also dug down as much as they could in the time available.

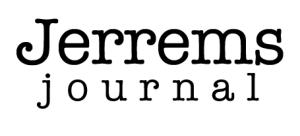

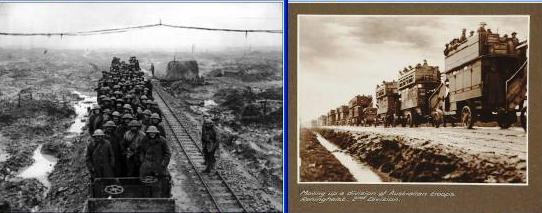

Railways.

Both sides had railway systems which ran north and south, set back a handful of miles behind the trench system so that they were out of normal enemy artillery range. Masses of materials, equipment and large numbers of troops could be transported along these lines, particularly under the shelter of night, and then into the combat areas on narrow gauge lines or roads. This was particularly important for the Allies when American troops and the enormous quantity of supplies from America started to arrive from late 1917 onwards.

| Percy’s lodgings |

As an officer Percy would have been assigned a dugout with a bunk to the rear of the trenchlines and a batman to assist him. The batman would have prepared his meals, cleaned his boots and clothes, run errands etc.

Battles

Briefly, after Percy was assigned to it, the battalion took part in the Battles of Messines, Polygon Wood and Broodseinde Ridge, followed by the infamous Battle of Passchendaele. These were all aimed at capturing “high” ground heavily defended by the Germans.

It would be difficult to imagine a starker contrast to the peaceful Kirklands area that Percy had left behind him.

| The Battles in more detail |

The following is a summary of the battles in which Percy served, drawing on the records of the Australian War Museum, with embellishments by me:

(a)Battle of Messines (7 June 1917-14 June 1917) was a successful British and Allies assault on the Messines Ridge, a strongly held high position which had been held by the Germans since late 1914. The initial assault was preceded by the novel detonation of 19 huge mines (with a total of 450 tons/tonnes of explosive) far below the German front line on Hill 60 which caused an estimated 10,000 German casualties. The blast was heard clearly in England. A film (“Beneath Hill 60”) was made recently about the tunnelling for the mines.

As you can see from the photo at the top of the Journal, some of the craters are still there almost 100 years later, the tranquil setting belying the original severity of the damage caused by the explosions.

The shockwave from the blast would almost have flung Percy out of his bunk if he was in bed (very likely at shortly after in the morning) and may have loosened some of the planks lining his dugout.

(b)Battle of Polygon Wood (26 September 1917-3 October 1917).

(Chateau Wood after battle pictured)

The Battalion was awarded Battle Honours for participation in the successful operations to secure strongly defended German positions in the vicinity of Polygon Wood and to consolidate positions on the Menin Road Ridge. The Battle was characterised by bitter fighting and fierce German counter-attacks.

(c)Battle of Broodseinde Ridge (4 October 1917).This was a large operation, involving twelve Allied Divisions, including the 40th Battalion. The Australian troops involved were shelled heavily on their start line and a seventh of their number became casualties even before the attack began. When it did, the attacking troops were confronted by a line of troops advancing towards them; the Germans having chosen the same morning to launch an attack of their own! The Australians forged on through the German assault waves and gained all their objectives along the ridge. It was not without cost, however. German concrete pillboxes were characteristically difficult to subdue, and the three Australian Divisions suffered 6,500 casualties.

(d) Battle of Passchendaele (12 October 1917).

Australian, New Zealand and British troops were involved in an unsuccessful attempt to seize the Passchendaele Ridge from the defending Germans. The fighting took place in the most appalling waterlogged conditions, which (as described by the War Museum) “helped render the name Passchendaele a synonym for slaughter”. A previous battlefield, the shell holes and old trenches were filled with water and mud. The 3rd Australian Division attempted to struggle forward to their objective with little artillery protection, the guns sinking into the quagmire when they were fired, and their exploding shells merely sending up geysers of mud.

In this battle 248 members of Percy’s battalion (a quarter of its complement) were killed, wounded or gassed.

The role of the Chaplain

Regardless of which side “won” a Battle the Chaplains (whether Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Roman Catholic or Salvation Army) were confronted in the First Aid Stations and Advanced Casualty Clearing Stations with a vast number of wounded or “gassed” men who had been dragged in from No Mans Land by stretcher bearers like my grandfather, or had staggered in with the help of mates.

Percy was known for his willingness to tend the men in the front lines, and one can only imagine the horrors which he would have encountered. He would have prayed with men who knew they were dying, writing down poignant messages to be sent by him to their loved ones, and comforting men who knew that they would be invalids for the rest of their lives if they managed to survive.

To reach the front lines Percy would have passed along communication trenches (known as “saps”) open to sniper and artillery fire and (particularly at Passchaendale) would have had to fight his way through the interminable energy-sapping mud to get to, and to travel along, the front trenches. Although he would have had sleeping quarters to the rear of the front lines he would still have been subjected to German shellfire.

| The contrast with Kirklands |

When he was in France, no doubt Percy would have thought about his family and the farm and gardens he had left behind. The lush farms and the backdrop of the Western Tiers mountains were such a contrast to the flattened moonscape of the battlefields, and on his farm neighbours would have been mowing the hay with scythes, as they had been doing for him in earlier years. Young Alec was proud that he could help the men with the mowing, but he and his little sister often found milking the cows quite difficult because they were not big enough to push recalcitrant cows into the bails.

After months of shellfire and mud his hobby of growing pink chrysanthemums amongst the towering poplar trees must have seemed like a distant memory.

| Conclusion |

OK,OK, OK. I hear you asking “What happened to the article about Percy?”.

The answer is that I thought it would be useful to give you a “snapshot” about the War but somehow the snapshot turned into a DVD. This will be useful for future articles involving descendants and friends of the Jerrems family in the First World War. Also I felt that the photos are very interesting, I spent quite a long time selecting them. Some I have not seen before.

So now we leave Percy in France, but he will soon return home to a hero’s welcome, to be described (I promise!) in a future edition of the Journal.