Dear Donald,

We welcome two new subscribers:

Rick and Darell Jerrems, Hobart, Tazmania. The Jerrems Journal featured several storylines in 2005 and 2006 about the early days of migration to the Hobart and Melborne areas of Australia.

Alan Fitz-Patrick, Amsterdam. By email, Alan advises Ray and me that we are probably unaware of the South African branch of the Jerrems family. Which is true, but we will try to cover this gap in future editions.

The Jerrems clan is small with makes updating Jerrems Journal mailing list fairly easy.

Here is a breakdown:

- We send to 44 active address on three continents, so far.

- 22 are located in the US; 20 in Australia and 5 in Europe.

- 20 are surnamed Jerrems (many are husband & wife or brothers and sisters).

| Young Nicoll the Tailor |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian

Introduction – Before Settling in the U.S.

This is the third article about Nicoll the Tailor and his forbears. In the second article we concluded with the information that Nicoll married Elizabeth Powell in 1841 in Norwich (north east of London) and they had a grand total of ten children. I said that I would follow this up in a later article, which I will now do.

This article also spends some time on the previously unsolved mystery of where Nicoll spent at least thirteen years of his life.

With the aid of everybody’s previous research and my secret weapon I have come up with the following list of children, born over a period of 23 years (Nicoll and Elizabeth were 20 when they married):

-

- ALEXANDER, b. 1841 in Foulsham (near Norwich, north east of London). Stayed in Australia.

- WALLACE (“Wally”), b. 1844 in Foulsham, stayed in Australia.

- MARY, b. 1846 in St Luke’s (London) d. 1928 in Santa Monica, California. Married William Jerrems in Melbourne in 1867, lived in Sydney until 1875, when family sailed direct to San Francisco.

- LETITIA, b. 1848 Birkenhead (near Liverpool), on West Coast. Stayed in Australia.

- ALFRED, b. 1849 Marylebone, London. Possibly died young.

- DONALD, b. first quarter of 1853 in St James, Westminster, London. Finally settled in New York.

- HELLEN, (“Nellie”), b. 1853 in St James, London, spinster, lived with Nicoll in Hampstead in 1891. This birth year may not be correct.

- EMMA, born 1856 or 1858 in Melbourne.

ANNIE, b. 1860 Melbourne, lived with Nicoll in Hampstead in 1891.

- FRANCES VICTORIA (“Fanny”), b1864 Melbourne, married Frederick Octavius.

- MATTHEWS (Saddler) in 1899, Hampstead, London. With Hellen and Annie she was an executor of Nicoll’s will. No children shown in 1911 Census.

| Lack of information |

Despite the earlier endeavours of my expert helpers and myself, we had not previously found any later information about half the children (Alexander, Wallace, Letitia, Alfred and Emma) from US and UK records, a situation which was unique and had me baffled. It was almost as though they had dropped off the face of the earth.

Nicoll’s obituary said he went to America in 1857. This marvellous piece of misinformation led me to spend a lot of time fruitlessly searching US records.

Recently I read extracts from the unpublished 120-page account of his family uncovered by Adam Marshall, written in the 1920s by a relative and extended by another relative in the 1950s. This account referred to Nicoll going to Australia.

Then came the revelation that Nicoll’s daughter Annie was born in Melbourne in 1860. This was discovered by the prolific Leila (whose family tree has about 19,000 entries), from the 1891 UK Census, but the significance did not dawn on me for several years.

The account uncovered by Adam and the reference to Annie being born in Melbourne led me to search Australian records, with the remarkable result that I discovered that Nicoll spent at least 13 years in Australia! So much for his obituary!

No census records have been retained in Australia, and other records are poor, so I have mostly drawn on other sources of information.

The pattern of the locations of birth in England

I use locations of birth of children to work out where a family lived over a period of time.

Looking at the births in England, at first glance one might conclude that the Nicoll family lived for a while in Norwich for the births of Alexander and Wallace (1841 and 1844), however this is where Nicoll’s wife Elizabeth was born, so it is likely that she went to her parents for help during the births. The birth of Letitia in Birkenhead on the West Coast is probably explained by the fact that her mother had relatives there, but the next three children were born in London. From this I would conclude that Nicoll and his family were based in London from 1841 until at least 1853.

Nicoll in Australia

My first port of call for my research in Australia was the 1856 Victorian Voters List (luckily one of the few Australian lists compiled in the 1800s which still exists), which showed Nicoll at Little Oxford Street, Tailor. Turning to newspaper records (the Melbourne “Argus”) I then traced Nicoll as having had a tailoring business in Melbourne until 1869.

It is possible that Nicoll, like my great grandfather Thomas, came out to Australia before the family.

| Melbourne in the 1850s and 1860s |

The discovery of gold in Victoria started in the early 1850s. This lead to a huge migration of intending miners by ship from overseas during that decade. A common pattern was for the diggings to be mined by individual miners until the gold obtained from alluvial deposits or shallow shafts was exhausted, after which bigger company operations were needed to recover the gold. The individual miners moved on to other discoveries, and then tended to eventually drift back to Melbourne, where they may have taken ships back to their homeland, or, more commonly stayed in Melbourne.

This pattern applied to my great great grandfather, Thomas Jerrems, who went to the first diggings at Mount Alexander in 1852, three days walk north of Melbourne.

It has been estimated that three in four miners had little success in finding gold. This led to a rapid increase in Melbourne’s population. Although Melbourne had only been incorporated as a city in 1847, by 1851 it had a population of 23,000, which, following the gold mining boom, grew to 60,000 by 1855 and 140,000 by 1861. This made it Australia’s largest city.

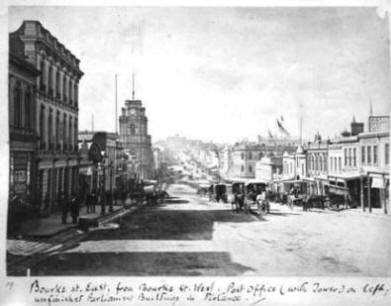

Unlike most cities, the centre of Melbourne had been planned, with streets in a grid pattern, the major streets like Bourke Street being very wide (see picture). Port facilities were nearby.

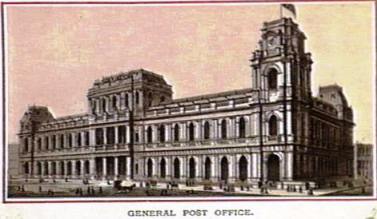

It was quite a progressive city, holding an International Exhibition (the first in Australia) in a huge new building in 1852 (see large building in the second picture in this article). Railway construction and other Government projects got under way. By 1862 railways had been built in Melbourne to Port Melbourne, St Kilda, North Brighton, Essendon and Hawthorn, and country lines were built to Geelong, Bendigo and Sunbury.

In the 1860s economic growth continued, the decline of mining being offset by the development of farming and manufacturing.

Turning to Nicoll, the population of 60,000 when he presumably arrived in Melbourne would have provided him with a strong commercial base for continuing his trade as a tailor.

| Nicoll’s addresses in Melbourne |

Nicoll carried on business in central Melbourne in (respectively) Queen Street, Collins Street East, Elizabeth Street and Swanston Street. I have found references to the family living near Little Lonsdale street in central Melbourne (see picture), and later in Grey street, East Melbourne (two miles/3km from the shop).

Later in the 19th Century Little Lonsdale Street became notorious for the gang warfare in the area, as described in the book “The Sentimental Bloke”.

| Transport |

Little Lonsdale Street intersected Queen Street, so he only had a short walk to his shop. When he moved to Grey Street he would have had about two miles (3 km) to travel. This was long before trams were introduced to Melbourne, so he would have had to walk or use horse transport.

In 1865, not long after the birth of Fanny, he advertised for a double seated buggy. With four children under the age of thirteen prior to the birth of Fanny it is possible that he already had a smaller buggy. Although a buggy would have been primarily intended for his family it is possible that he used it for transport to his shop as well. In 1851, in London, he employed three servants. If he had a similar number in Australia one of the servants would have looked after the horse and buggy and would have driven him to the shop.

Nicoll’s advertising style

Initially Nicoll’s advertising was conservative, but later it gained momentum, reminiscent of his later style in America. The most notable references were as follows.

In December 1865, he made his first reference to suits being made in a day:

“NICOLL’S SUIT of BLACK CLOTH to measure, £4 ; trousers, 26s. Made in six hours, if required.” In January 1869 he made his first use of his later famous business name: “NICOLL THE TAILOR”. Was the Melbourne foray successful?[put photo of Exhibition Building here]

I would say that Nicoll was not outstandingly successful, otherwise he would have stayed in Melbourne rather than embark on another laborious four months voyage back to the Old Dart! Also, he was made bankrupt on two occasions in the early to mid 1860s. On one occasion he blamed (in part) “family illness” for his predicament. Another hint about his lack of success (comparatively speaking) in Australia is possibly the later omission of any reference to his career in Australia in his obituary.

On the other hand his business was run on a fairly generous scale , in 1860 his shop rental was nine pounds per week, indicating large premises.

| Nicoll’s political views |

In the 1800s there were the two opposing policies of “protectionism” and “free trade”. The British Government favoured free trade for many years, and many historians blame that policy for the enormous loss of life caused by the Great Potato Famine in Ireland (1838-1842).

In simple terms protectionism involved the setting of tariffs on imported goods to protect local industries. In Australia the Victorian Government favoured “protectionism”, which could have placed import duties on Nicoll’s imported goods. and the NSW Government favoured free trade.

Nicoll made his views known in no uncertain fashion in the following amusing diatribe against “protectionism” published in the “Argus” in December 1865 (note that the reference to “traveller” means a travelling salesman):

“NICOLL, TAILOR, 124 Elizabeth-street, two doors from Bourke-street, is sorry to be the first to inform free-traders, shareholders, and others interested in the company formed for a direct line of railway to the moon, that the project is likely to fail.

Nicoll’s traveller, with samples of tweeds for suits to measure from £8, went express to Moonland to secure orders for suits for Christmas, but on reaching the Heads (of the moon) he was met by the man in the moon, who informed him the inhabitants had resolved to exclude every trader from their planet. “Why,” says Nicoll’s traveller, ” for Christmas suits to measure from £8 ; this is worse than Japan or China, or the Cannibal Islands.” Says the man in the moon, ” It’s no use losing your temper, we are all-sufficient to próvide for all our wants, and by excluding you we shall grow rich, prosperous, and happy.” Says Nicoll’s traveller for Christmas suits “That’s all moon-shine, old boy. But I tell you what I’ll do; I don’t want cash for my goods, I’ll take some of your moonish notions, if they are worth anything ;” but says the man in the moon, “We cherish our moonish notions too much to part with them ; we may indulge in free speech, but free trade and free thought will find no chance here ; therefore, go back to your own planet and confine yourself to your own little corner of it.” At this Nicoll’s traveller for Christmas suits to measure lost his gravity, and has not yet recovered the shock to his sides from the fit of cachinnation he fell into.

Nicoll believes protection means communism, isolation, and barbarism. Nicoll believes competition is progress, unites nations, advances civilisation ; and the scarecrow that is stalking about the country must be the ghost of protection, for sure it was dead and buried years ago in the old country, and Nicoll intends to lay the ghost at the coming elections, and hold a general wake over him, playing the Scotch fiddle over his grave. Nicholl, tailor, 124 Elizabeth-street.”

Nicoll the Tailor’s character

Adam Marshall’s account refers to Nicoll as follows:

“Alexander, the only son, tradition says was not of a steady disposition. He was shipped off to Australia.”

This reference has the connotations of a young wayward son being put on a ship to Australia as a “remittance man” for some infringement. On the contrary Nicoll had had four children by 1853, when he was 31, but it is correct that he did go to Australia. Perhaps not being of a steady disposition (if true) was an advantage for a person with entrepreneurial ambitions, although he did not achieve significant success as a tailor until the 1870s after he went to the United States.

Conclusion

It has taken me longer than I expected to get this far. I will give a brief account of some of his children (concentrating on the ones who stayed in Australia) in a future article.