Dear Donald,

| MOUNTAIN HUTS (PART 2) |

Ray Jerrems, Our Genealogist, Historian, and Mountain Adventurer

Introduction

In my first article, in the January 2013 Journal, I described the method of construction of typical mountain huts in the New South Wales Snowy Mountains.

What I did not mention was the fact that the stockmen’s huts (unlike the miner’s huts) were only used by the stockmen for a peak period of about two weeks a year, during mustering time in autumn prior to arrival of the first snows. In that period the stockmen were out from dawn to dusk locating, mustering and yarding the stock which had been roaming the high plains since being brought there in spring. There was a need for maximum capacity, at the expense of creature comforts.

Unlike Victoria, where stock are still allowed to be run on some of the high plains, in New South Wales nearly all the high lands were integrated into a National Park in the 1960s and 1970s.

Transport

A significant factor in the choice of building materials and food was that before the end of the Second World War (after which four wheel drive vehicles became available) most huts could not be reached by vehicle, and in fact some still cannot be reached by vehicles. As described in my previous article, logs were brought in by bullocks, and lighter building materials and provisions were brought in by packhorse. This put a premium on the use of local materials, except for window glass, galvanised iron and angle iron for fire places, all of which was brought in by packhorse. This emphasis on local materials also helped reduce the cost of building construction, even to the extent of using hardwood pegs in place of nails.

After the Second World War a range of four wheel drive vehicles became available for purchase as army surplus. These included the light Jeeps, Landrovers, Austin Gypsies and Austin Champs. However these did not have a large carrying capacity, a niche filled by the famous Blitz Wagon.

| The Blitz Wagon |

The “Blitz” had a good carrying capacity and an excellent clearance, without being too cumbersome like the bigger six wheel drive army transports. After the War it became the rural workhorse, being used extensively by timber getters, fencing contractors, farmers, bushfire brigades and outback mailmen and carriers etc. When equipped with a winch it could extricate itself from bogs and carry out a multiplicity of roles like pulling out stumps, tensioning fences and stockyard cables etc.

I remember the Blitz used by the Carlon family in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. Their only access to their farm was originally by horse trail down a mountain, but this was later augmented by a Blitz which was parked at the top of the mountain for use when required. The track used by the Blitz was so steep it was difficult to imagine that a vehicle could use it.

The stockmen

The stockmen who built most of the huts and lived in them were a tough breed who had grown up on hard work in extreme conditions. They rode hardy mountain horses and worked long hours when necessary. I met some of them and will devote a separate article to my recollections.

Roofing and chimneys

In the very early huts sheets of bark or timber shingles split from logs were used, but corrugated iron was used later, often simply nailed over the bark or shingles of a pre-existing roof.

Bark roofs lasted as little as ten years, with shingle roofs lasting somewhat longer. Although it is difficult to establish with certainty how long the corrugated iron lasted on the roofs of the huts, I estimate that it lasted up to seventy years, with the occasional eighty years. This was a dramatic improvement over bark and shingle roofs. There were actually different grades of galvanised iron, with the heavier galvanising obviously lasting longer.

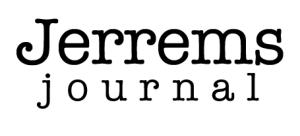

Early chimneys were made of stone if it was available. As you will see from the photo of Wallace’s Hut at the top of this article, later chimneys were made of galvanised iron nailed onto a timber frame. The upper parts of the chimneys tended to be separate from the hut to reduce the risk of a fire in a chimney spreading to the main part of the hut.

Windows

Although the windows in most huts are now made of glass, for economy reasons windows in some huts (particularly earlier huts) comprised shutters hinged at the top which swung out and up and were propped up with poles. Some early widows were also made of hession.

| Furniture |

Stockmen were masters of innovation, using everything available. Trestle tables and bench seats were made from split timber, and supplementary furniture like storage cupboards were made from butter boxes and kerosene, honey or biscuit tins. Single seats could be made from logs on legs, or more elaborate armchairs and rocking chairs made from saplings, bags and fencing wire.

Beds came in a variety of forms, from beds with plank bases, hessian from the versatile potato, corn or chaff bags slung between horizontal saplings, to iron beds with wire bases after the First World War. Most of the wire beds would have had horse hair mattresses but these deteriorated over the years and were burnt, leaving a quite Spartan bed.

Hut liningsThe huts (particularly slab huts) needed some method to keep the wind, rain and snow from coming through the cracks. Powder snow had a habit of finding its way through the tiniest of cracks.Clay could be packed in the cracks, or the walls could be lined with hession (obtained from old bags) or old newspapers coated with flour paste.

Newspapers provided a handy way of dating the construction of huts, in one instance in the early 1960s I found newspapers dated in the 1880s in a hut in the Blue Mountains near Sydney.

Water supply

Few huts had water tanks because the roofs did not have guttering. Water had to be carried from a nearby spring or creek and stored in a drum which sometimes contained a tap.

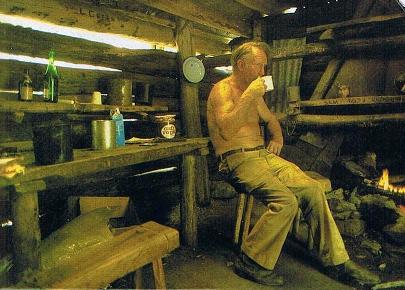

| Baths |

I doubt whether taking baths was a strong point for stockmen. I have seen cases of stockmen bathing in a 44 gallon drum standing over a fire but this was probably the exception.

Despite this, I found a full sized bath sitting in O’Keeffe’s Hut near Mt Jagungal in about 1969 and Klaus Hueneke reports seeing one at Wallace’s Hut in the early 1980s. Perhaps it was the same bath. A stumbling block to the use of the baths was that in both instances water had to be carried from a nearby creek and there was no boiler or similar heating system in the hut.

As a matter of interest one night a friend and I decided to test the bath at O’Keeffe’s Hut. Initially we towed the bath, which was not connected to anything, into the doorway, with the plughole projecting outside the doorway, so we could take it in turns to lie in the bath and admire the stars through the doorway. When we had finished we simply pulled out the plug.

We boiled up water in a four gallon drum and added it to cold water we had poured into the bath. Needless to say the bathwater needed to be warmed up continually with hot water, a losing battle.

We concluded from this scientific experiment that there was no way that the average stockman would have spent so much time and effort to have a lukewarm bath, leaving us with the puzzle of who had brought the bath in, and why!

Grey Mare Hut, built by miners, had a sauna, a partial solution to the question of bathing in winter.

| Wildlife |

Although we saw brumby (wild horse) tracks occasionally, most wildlife we saw comprised the small (or comparatively small) pestiferous varieties. The amiable wombats delighted in digging large burrows under the huts, and visitors waged a continuous war with the native marsupial rats and the possums.

The rats delighted in raiding food supplies brought into the huts during summer by stockmen and intending skiers. One solution was to hang the food in bags suspended by wire from the roof rafters. However even this did not always work. One winter in Mawsons Hut I saw that the previous summer bags of provisions had been raided by gymnastic rats which must have climbed along the rafters and slid down the wires.

Here is the cutest photo of a wombat I have ever seen. It was taken by Alan Levy and is shown on his website http://members.pcug.org.au/~alanlevy/KosciHuts.htm with the following description:

“Friendly baby wombat on White’s River fire trail – Jul 95. We did a ski tour from Munyang to White’s River Hut and The Rolling Grounds. On the return trip down the road we came across two wombats. The baby wombat came up to us of its own accord and wandered around us and sat momentarily on the ski, while its mother watched nearby”.

| Cooking and heating |

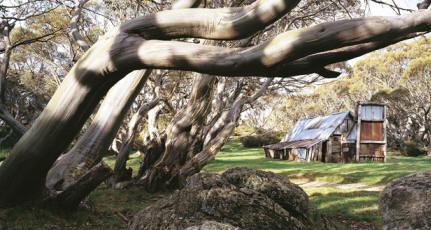

Most huts had huge fireplaces (see earlier photo of interior of hut), used for cooking and heating, although some later huts had pot bellied fuel stoves.

Although the huts had chimneys all the huts had a perpetual smoky smell, which seemed to be etched into the hut’s interior and furniture. At first newcomers found this to be curious, but after several days holed up in a hut due to bad weather everybody smelled rather like smoked hams anyway.

The cooking utensils used were largely determined by the method of cooking used. For open fires in the early days large prune tins with wire handles were popular as billy cans, and jam tins made good mugs. Later, large cast iron pots were popular on fuel stoves, and they could also be used on the open fire if they could be suspended from a hinged bar which swung across into the fireplace.

This applied particularly to the large iron pot somewhat misleadingly called a “camp oven”. It was what we would now call a “slow cooker”. It had the attribute that due to the thickness of the metal it was virtually impossible to burn the contents, even at the hands of the most novice cook.

The photo shows a camp oven with its heavy lid removed.

| Lighting |

Candles and kerosene hurricane lamps were the most common forms of lighting. The lamps had the advantage that they were unlikely to cause a fire and could be carried outside in windy weather. On the other hand candles were much lighter to carry.

Food

Difficulty of access meant that the food was rudimentary.

Where a hut could be reached by vehicle tinned food would often have been used by the stockmen and their dogs. Otherwise, due to storage problems the only vegetables eaten by stockmen were usually potatoes and onions. However the stockmen were very resourceful when it came to obtaining meat. Although it was simple for stockmen to knock off an old sheep a non-stop diet of mutton became monotonous, regardless of whether it was boiled, roasted, grilled, fried, minced or curried. The stockmens’ dogs were not given any options.

A lot of ingenuity was used for this, and discussions on the favoured method would have been frequent, just as bushwalkers used to discuss how to cook dried vegetables in later years. Therefore the stockmen supplemented their diets pragmatically with rabbit, possum, wallaby, wombat, and cockatoo.

Instead of bread (which required the use of yeast) damper was almost universally used. This could be cooked in a camp oven or in a metal dish equipped with a fitted lid.

As can be seen from the camp oven photo, dampers were very appetising, particularly when cooked the night before, as my wife and I often did. Although the simplest recipe is flour and water with a pinch of salt, use of milk or milk powder, and sugar, brings it up to a lighter texture similar to scone. Simply serve with butter and jam.

Most huts had rabbit traps, and at least one of the stockmen would have carried a 22 rifle which could be used for hunting. Rabbit traps had the advantage that they could be set quickly and checked at “off peak” times. The advantage of a light 22 rifle was that it did not demolish small game.

| Firewood |

“Hut etiquette” dictated that although the huts were stocked with wood by users in summer, unless there were strong reasons preventing it, winter users were expected to replace what they used also, where the huts were below the tree line. Snow gums tended to have some dead branches, which could be accessed in winter by climbing the tree.

Conclusion

I have fond memories of staying in the mountain huts, particularly in winter when there was deep snow outside and blizzards could last for days. The rustic nature of the huts added to their charm.

In a later article I will tell you about some of the characters I met, and some who I would like to have met (including Jack Lovick). Jack was one of the most famous horsemen of the high plains, who organised the spectacular horse riding scenes in the iconic Australian film “The Man From Snowy River” (Jack is the man drinking tea in the photo of a hut interior). In an epitaph he was described as “The quick-witted, strong-willed mountain man who loved attempting the impossible on horseback, (and) was regarded as the last of the original mountain cattlemen.”